Mourning was the first occasion that the first-generation graffiti writers (1968-1978) of the Bronx all convened. Held at the Bronx’s Valentine-Varian House last December, the pseudo-wake for their first-generation writer companion Daniel J. Bonterre, or Dr. Soul 1, wasn’t so much of a grievous occasion as it was one flush with joie de vivre. In what is now a two-hour long documentary video, the graffiti writers, including AJ 161, Bomb 1, Butch 2, Chain 3, Charmin 65, Comet 1, Riff 170, and Staff 161 among others, trace both Bonterre’s and their youthful spray-painting exploits in the Bronx.

The video’s curator and first-generation writer, Staff 161 or Edward Jamison, boils down the occasion’s ambitions to this thesis in the video: “Our generation is slowly dying out, and we have to acknowledge those that are still here and those that are gone.”

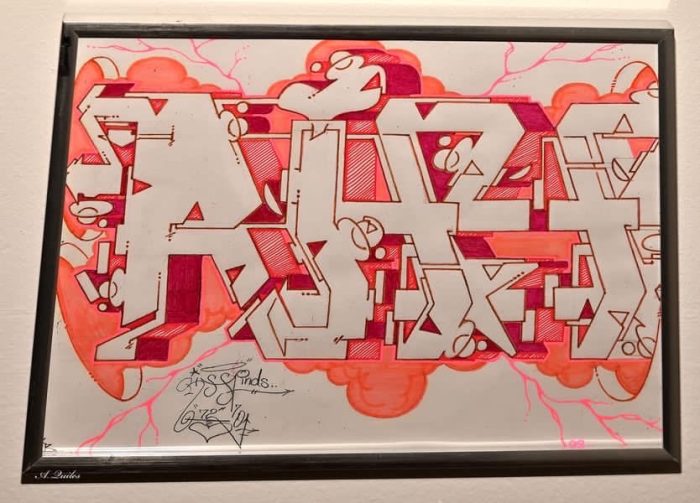

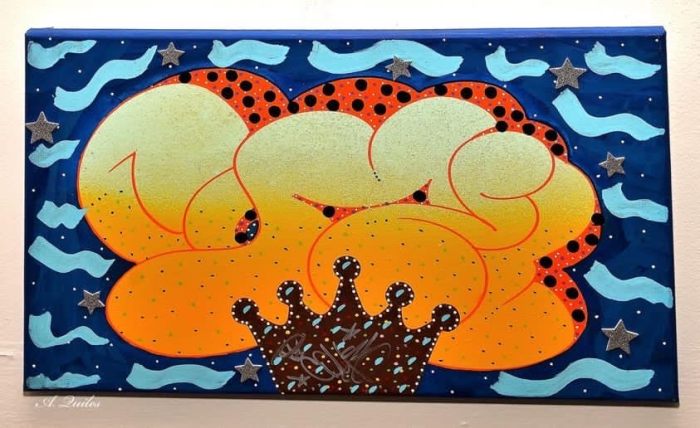

The same impulse—saluting the projects of first-generation taggers in the Bronx—drew the crew together just seven months after their untraditional rite. The exhibit A Bronx Writers’ History: 1968-1978, now on display at the Museum of Bronx History, was the conditional by-product. The two dozen spray-painted canvasses in the exhibit are all stamped with the writers’ signature tags and identifying iconography. The exhibit sets forth Staff 161’s lightbulb-crowned skull and crossbones, AJ 161’s boxy tag, Comet 1’s puffy lettering, Riff 170’s futuristic, hi-tech tag, Chain 3’s stumpy model of New York City, and more.

For Staff 161, the curator of the exhibit, the central fixation of the exhibit’s visual works is to extend the mythology first outlined during the wake: Of course, the exhibit frames the first generation of Bronxite writers in the late 60s and early 70s as a cultural cohort that dealt in the currency of street cred. (“You would automatically have this importance and purpose just by having your tag all city,” Staff 161 noted.) But A Bronx Writers’ History also recognizes writers as a quasi-political organization with aspirations to bring disavowed Bronxites—born into a locale and period of economic downturn, deindustrialization, and high crime—into the city’s consciousness. Tagging, on street signs, alley walls, bridges, and optimally a cross-borough IRT train, was the iconographic reminder that Bronxites were there, still eking out a living.

“The people from that community were not considered part of the mainstream order or population of the city mainly due to poverty or other undesirable social [activities] like street gangs and drugs,” Ford Apache-native Staff 161 told The Bronx Times, later explaining the psyche of the young graffiti writers who tagged, “I’m here. I might not be significant on your rating scale because I am here in this particular neighborhood or environment, but I am here, nonetheless. I don’t intend to be ignored or made insignificant.”

Even if the aesthetics of graffiti writing in its first metropolis go-round aren’t maintained in the exhibit—graffiti writing was a largely anti-establishment medium that rejected canvassed art—a similar sentiment remains. A Bronx Writers’ History: 1968-1978 reproduces the mythos of a disenfranchised, fraternal youth with limited resources, too early to have been documented.

“Graffiti art is the most unique and original youth culture offering really in the history of folk art and youth movements,” Staff 161 said, adding, “You [the graffiti writer] are part of that metropolis, and you have something to offer in that metropolis.”

For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes