As the first supervised drug consumption facilities in the country begin operating in Manhattan, Bronxites living among the highest overdose rates in New York City may wonder when the centers are coming their way.

There are no concrete plans for the sites in the Bronx — yet.

The centers — called overdose prevention centers (OPCs) — allow people to bring in illicit drugs and use them with clean needles under the supervision of workers at the ready with naloxone, an overdose reversal drug. There are more than 100 centers across various countries; the first two in the United States opened in Manhattan on Nov. 30.

State Sen. Gustavo Rivera, a progressive representing the Bronx and chairman of the state Senate Health Committee, told the Bronx Times that a few providers are being discussed for OPCs in the Bronx, but they don’t have the operational level necessary to open yet.

The senator said controversy surrounding the facilities stems from a mistaken belief that addiction is a moral failing that should be treated as a crime. Addiction, instead, is a disease and should be treated as such.

“They are compelled physically to use this substance,” Rivera said. “That is what addiction is. So just because you push them into a place you can’t see them, they’re still going to use.”

When stigmatized, people hide their addiction, leading to overdoses and deaths, he said.

Rivera sponsored a bill in January 2019 to roll out an OPC program, but it didn’t garner enough support. He plans to advocate for two fresh bills in Albany, one to create an OPC pilot program and the other to authorize and regulate the programs statewide.

But Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, could allow the centers more expeditiously through executive action, similar to what Mayor Bill de Blasio, a progressive, did in New York City, Rivera told the Bronx Times.

Out of more than 100 OPCs in the world, there hasn’t been a single death at one of the centers, Rivera said — a claim echoed by de Blasio’s office.

The centers have intervened in 36 overdoses as of Sunday, Dec. 12, a spokesperson from OnPoint, the group that runs the Manhattan centers, told the Bronx Times.

But not everyone is welcoming the program with open arms.

Julia Cruz, a social worker and CB2’s first vice chair, said a center would be “horrible” for the district when the city health department presented information about the centers to CB2’s Health and Human Services Committee on Dec. 6.

She said an OPC would serve as an invitation to drug dealers and people who are addicted to drugs to come into the neighborhood.

“I’m just concerned about the community,” Cruz said. ” …I’m concerned about bringing people in, and it seems like it’ll be a revolving door — use your drugs, leave.”

She also questioned the effectiveness of the centers.

“Are you really helping them, or is this something to pacify them and let them use their drugs?” she said.

Michael McRae, acting executive deputy commissioner of the health department’s mental hygiene division, said that 30 years of data from other countries show a reduction in overdose deaths in neighborhoods with the centers, as well as a reduction in public drug use, littered needles and drug-related crimes. He also said people who use the centers already live nearby and don’t travel 2-3 miles to get to them.

While there hasn’t been a data analysis to track where people utilizing the Manhattan facilities are coming from, a spokesperson for OnPoint attested that Bronxites have been using the program’s services on-site and through mobile van outreach in the Bronx. All of OnPoint’s health and overdose prevention services are available at the vans, except supervised consumption.

When board members questioned McRae on whether the centers help people quit drugs, he said data shows people are more likely to get connected with services, and not overdose and die.

“Not dying feels like a higher-order goal than making sure the person gets off of drugs in that moment in time.” McRae said. “The idea is that over time, they build a relationship and get connected to services.”

The centers can connect people to treatment, medical care and social services, receive counseling, and get basic necessities, a city health department spokesperson told the Bronx Times.

McRae said an OPC would have given his father, who died of AIDS and was a heroin addict, a better chance of living.

CB2 Chairman Roberto Crespo argued that the neighboring Community District 1 — which includes Mott Haven, Melrose and Port Morris — would need the center more than CD2 — which includes Hunts Point, Longwood and part of Morrisania — and that public containers to deposit needles in CD1 were overflowing while CD2’s were barely used.

McRae said there are still significant concerns in CD2.

“We believe that this is something that really should be at multiple jurisdictions around the city,” he said of the OPCs.

City Councilwoman Diana Ayala, who represents much of the South Bronx and East Harlem, told the Bronx Times the centers need to be in every neighborhood that needs them in order to be most effective. She said the Bronx desperately needs the centers, particularly in the South Bronx.

“The numbers are really high and it merits our immediate attention,” she said.

In 2020, fatal overdoses were at an all-time high since reporting began two decades ago, at 2,062 deaths citywide, according to the health department. The first quarter of this year had 596 overdose deaths, compared to 456 last year during the same period.

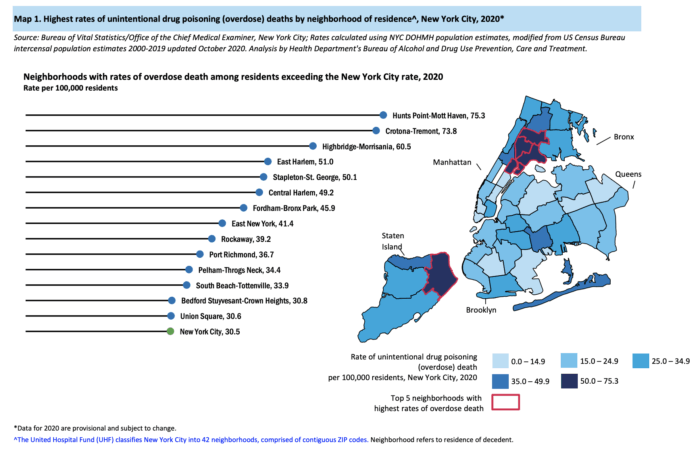

The Bronx had the highest rate of overdose deaths out of all the boroughs in 2020, at 48 per 100,000 residents, compared to 25.2 in Manhattan. The numbers amplify in the South Bronx, with 68.7 overdose deaths per 100,000 residents.

In Hunts Point and Mott Haven, the numbers rose to 75.3, and in Crotona and Tremont, it was 73.8.

Ayala said conversations have been initiated about bringing centers to the Bronx, which will need to continue under Mayor-elect Eric Adams, who said he plans to open more OPCs.

OPCs in New York City have the potential to save 130 lives a year, according to the city’s feasibility study.

The Manhattan sites launched on Nov. 30 in conjunction with de Blasio’s office and NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The centers are run by the Washington Heights CORNER Project and New York Harm Reduction Educators, in Harlem — private providers that are merging into one organization called OnPoint NYC.

The supervised drug-use sites don’t just allow injections but also allow smoking, snorting, swallowing or other means of using drugs, a spokesperson for the Manhattan centers said.

OnPoint would like to expand in the future but doesn’t have plans for additional sites, the spokesperson said.

McRae told CB2 that there are no firm plans for Bronx centers, but the health department is looking forward to expanding. A spokesman for the mayor’s office told the Bronx Times on Friday there are no further expansion plans to report.

Reach Aliya Schneider at aschneider@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4597. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes.