New York City’s housing crisis is no secret and the city’s low-cost housing landscape remains extremely difficult to navigate, including a housing lottery system theoretically devised to provide a solution for the dire need for accommodation.

A problem that has been brewing for decades, the housing crisis continues to get worse, with vacancy rates dropping to 1.4% citywide and under 1% for units priced $2,400 or lower, according to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).

Meanwhile, rents continue to climb, with a 2024 report from New York City Comptroller Brad Lander finding that the median asking rent for available apartments across NYC was $3,500 a month. A household would have to earn $140,000 per year in order to afford such a unit based on the nationwide standard, suggesting that households should spend no more than one-third of their income on housing.

In recent decades, the city and state have implemented numerous initiatives to combat the affordability crisis, including widely promoted housing lotteries, which give middle-income New Yorkers a chance to apply for below-market-rate units in new developments.

However, the lottery system — overseen by HPD and accessed through the online NYC Housing Connect platform — is overwhelmed with applications and feeling the strain of the crisis.

In 2024 alone, Housing Connect received six million applications for just 10,000 available units.

HPD acting Commissioner Ahmed Tigani testified at an April 29 City Council hearing on the Housing Connect system and noted that each new development typically receives an average of 16,000 applications—underscoring the scale of the city’s ongoing housing crisis.

‘Affordable’ housing that isn’t all that affordable

Bronx Council Member Pierina Ana Sanchez, Chair of the City Council’s Committee on Housing and Buildings, said a big problem with the lottery system is that they are not affordable to large swathes of the city’s population – and likely never will be.

That is because “affordable” rates offered through the housing portal are determined by Area Median Income (AMI), a highly controversial and complicated figure calculated annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

HUD currently defines 100% of the Area Median Income (AMI) for a family of four in New York City as $162,000—a figure derived through a complex set of formulas that incorporates higher-income counties outside the five boroughs, including Rockland and Westchester.

In contrast, the actual median income for a family of four living in New York City is just $79,713, according to the latest U.S. Census data.

As a result, a unit marketed by HPD at 50% AMI—typically categorized as “low-income”—is in fact roughly aligned with the true median income of New York City residents. For example, HUD pegs the AMI for a single-person household at $113,400, which is more than twice the city’s per capita median income of $50,776.

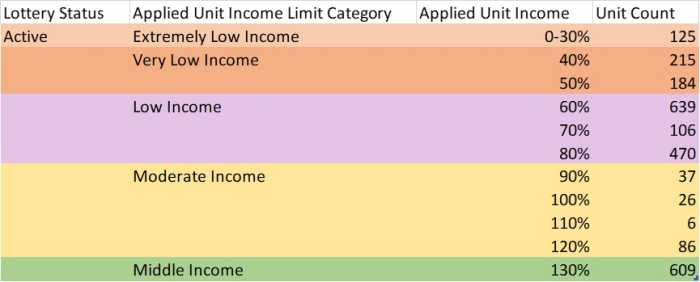

Current listings on the Housing Connect portal skew toward higher-income earners. Of the 2,503 available units, nearly 30%—or 729 units—are priced for households earning 100% AMI or more based on HUD income figures. In contrast, only 525 units, or 20% of the apartments on offer, are available at or below 50% AMI, according to HPD data.

In effect, nearly 80% of HPD-listed units are only available to households earning above the true citywide median income.

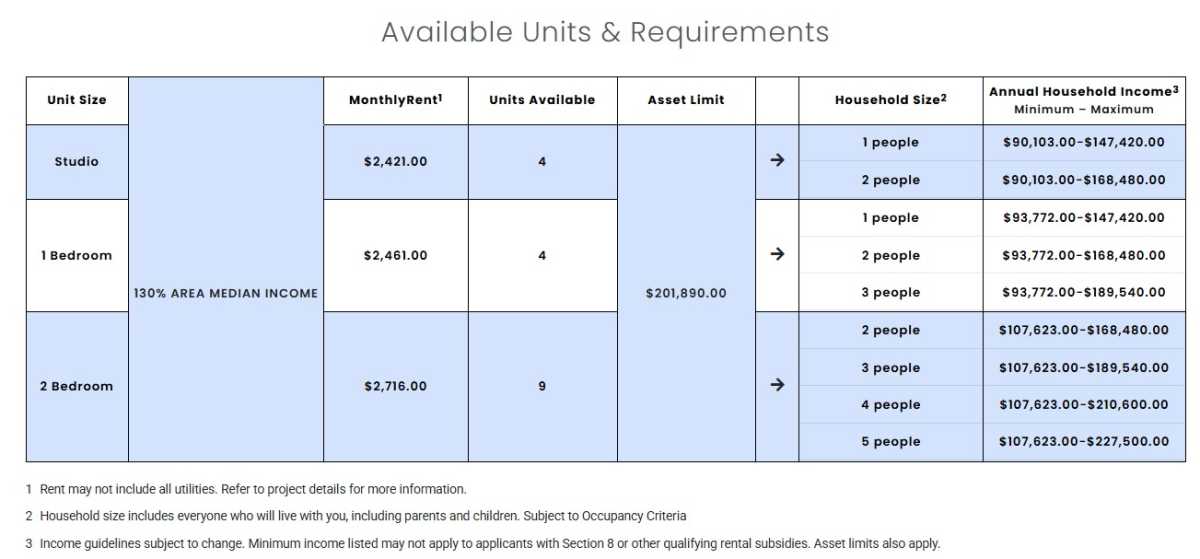

A major development at 21-04 Ryer Ave. in the Bronx, offering 17 units through the city’s affordable housing lottery, requires a family of four to earn at least $123,086 to qualify for a two-bedroom apartment—priced at $3,590 per month. That rent exceeds the citywide median, as cited in the Comptroller’s latest report. The same family can earn up to $210,600 and still be eligible, reflecting the 130% Area Median Income (AMI) threshold.

The building is located in a borough where the median household income is just $49,036. All 17 units in the lottery are priced at 130% AMI, with advertised rents of $2,421 for a studio and $2,716 for a two-bedroom. To qualify, applicants must earn at least $90,103 for a studio and $107,623 for a two-bedroom.

For context, a household leasing a two-bedroom unit at Ryer Avenue would spend $32,592 on rent annually—just $16,444 less than the typical household earns in the borough, not including taxes.

Most units offered via the lottery system are largely unattainable for New Yorkers earning below the median income.

Alex Schwartz, professor of public and urban policy at The New School, said AMI is a “huge issue” but noted that there is little that the city can do as the federal government has classified New York as a high-cost housing market. Schwartz also noted that the median income of low-income neighborhoods, such as the South Bronx, is far lower than the citywide median, which “exacerbates” the issue.

The pitfalls of Housing Connect

Housing Connect was initially hailed as a groundbreaking tool in the fight against New York City’s housing crisis. But more than a decade later, the city’s housing lottery system is showing its limitations.

Sanchez said the system is flawed and no longer serves its purpose. With just 10,000 affordable units available in 2024 and a staggering six million applications submitted, she notes that the odds of securing housing through the platform are minuscule.

Sanchez said the system also exacerbates inequality, given the income requirements. “It’s absolutely not [equitable],” she said. “It’s heartbreaking.”

Sanchez also pointed out that less tech-savvy applicants often miss important notifications from Housing Connect, which may be filtered into spam or junk folders. She noted that in some cases, even an elderly resident who is selected for an affordable unit could lose the opportunity simply because they never saw the message.

She also told amNewYork that she has seen applicants miss out on a unit because they made a slight mistake when submitting documents.

Furthermore, Sanchez states that Housing Connect is supposed to have a system that filters available units based on a person’s income, only showing applicants units that they can afford. The reality, however, is that Housing Connect often does not filter out units and sends people advertisements for apartments that they are not eligible for.

“One of the constituents who joined us [for the April 29 city council hearing] said, ‘It just feels cruel. It feels like you’re laughing at me. It feels like the City of New York is laughing at me and my situation,” Sanchez said.

Tigani, with HPD, told the Council during the April 29 hearing that HPD is taking steps to streamline documentation requirements and reduce the need for excess paperwork. For instance, it has just reduced the number of pay stubs required for approval.

Applicants with jobs are now required to submit just one month of pay stubs, a significant change from the previous requirement of up to six months.

He also noted in the April 29 hearing that HPD will carry out a comprehensive overhaul of the Housing Connect system to improve its functionality and user experience.

HPD Press Secretary Matt Rauschenbach said the housing lottery is “central” to the department’s efforts to make housing more accessible for New Yorkers.

“We are focused on engaging and listening to New Yorkers and are constantly looking for ways to improve the process and get more New Yorkers and their families into housing,” Rauschenbach said in a statement.

New Yorkers Struggle to meet income requirements

Many New Yorkers who testified at the City Council’s April 29 hearing touched on this issue, speaking of how they have had to work multiple jobs or work 50-hour weeks just to make enough money to be eligible for even the cheapest units offered through the portal.

Valentina and Victor Mejia, an elderly couple from the Bronx who have been applying on Housing Connect since 2012, testified about the challenges of applying for the lottery. Valentina stated that she has had to take up three jobs simultaneously in order to meet the income requirements for the application.

The couple has also had to live “between cockroaches and mice” in their current accommodation while they wait for their applications to be processed.

“I can’t keep doing this,” she told the hearing.

Milagros Salazar, a low-income health worker living in the Bronx, told the hearing how she applied to 63 lotteries before eventually being accepted for an affordable unit. She said she often worked 50-hour weeks in order to meet income eligibility for the lottery, stating that she constantly suffered from “anxiety” throughout the application process.

She also said she was disqualified from one apartment because her income was $100 less than the minimum requirement and contended that very few units are offered to applicants earning under $40,000 per year.

Sonia Simpson, a member of Bronx advocacy group Affordable Housing Opportunity Right Away (AHORA), has been applying for units through Housing Connect for years but said there are few units that she is eligible for based on her income. She told the hearing that she finds the housing portal difficult to use, stating that she especially struggles to update her applications on her phone.

Furthermore, Simpson, who has signed up to be notified of units via e-mail, said she receives “constant emails” from Housing Connect for units she cannot afford or is not eligible for based on her income.

“This is frustrating, and I can only imagine how frustrating this must be for the elderly or non-English speakers,” Simpson told the hearing.

Alex Martinez, who testified on behalf of the Kingsbridge Heights Community Center, which has provided assistance to over 2,000 Bronx residents with applications since 2017, told the hearing that the Housing Connect system is often glitchy and difficult to use for people with limited digital literacy.

“The portal has grown more and more glitchy, and the website is often down,” Martinez said. “It is a disservice to the clients who come to our weekly walk-in hours, only to be turned away because the website is not working.”

For the small number of applicants who win an affordable housing lottery, the process remains far from straightforward and is often burdensome.

According to testimony from Tigani at the April 29 hearing, applicants can wait anywhere from 12 to 15 months between submitting their application and moving in. The average wait time between selection and lease signing stretches 109 days, as noted in the 2025 Mayor’s Management Report.

Addressing the problems

Sanchez has introduced three bills to improve Housing Connect. Two of those bills focus specifically on improving the user experience and assisting people with limited digital literacy.

Intro 1265, for example, would require Housing Connect to notify applicants if they are successful or not by both email and text, while also allowing applicants to assign a designee to handle their applications. Additionally, another bill, Intro 1266, would create a city-funded in-person assistance program to help renters through the Housing Connect application process.

There is currently no such program funded by the city, with non-profits and other agencies stepping in to help reduce some of the demand for Housing Connect assistance.

Vacant units

Sanchez’s final bill, Intro 1264, seeks to reduce the long delays in filling the units vacated by lottery winners—also known as re-rentals. Until recently, HPD required these units to go through the Housing Connect lottery system, a process that could take an average of 16 months before a new tenant moved in.

In response to mounting criticism, HPD began issuing temporary waivers allowing landlords to list re-rental units on external platforms like StreetEasy and Craigslist—but those waivers are only valid for one year. Sanchez is now pushing for a more permanent fix to prevent such long-term vacancies.

“A 16-month wait for a perfectly good apartment that many families would die to live in is unacceptable,” Sanchez said. “Progress on that is great… but what happens after the year? Do we go back to 16-month waits?”

No easy solution

Rachel Fee, executive director of the New York Housing Conference, meanwhile, said hefty building costs in New York City make it difficult for developers to offer low-cost housing.

“You have to think about how much it costs to operate a unit,” Fee said in an interview.

Given current construction costs, she said it is unrealistic to expect that a large number of units could be built and rented to very low-income populations—leaving tens of thousands of New Yorkers without viable housing options.

She explained that under the one-third income rule, a household earning less than $30,000 annually would need a unit rented at well under $1,000 per month for it to be considered affordable. As a result, she argued that expanding housing assistance programs like Section 8 is the only viable path to securing stable housing for those classified as “very low income.”

Sanchez, meanwhile, pointed out that the median income in her Bronx district is just $25,000 for an individual, leaving many of her constituents effectively excluded from the affordable housing lottery. She emphasized that without city subsidies to help developers reach deeper levels of affordability, these units will remain out of reach for the city’s lowest-income residents.

“It’s like a false victory lap when a mayor or a governor or anyone says, ‘We’re building deeply affordable housing,’ when you are excluding my entire community,” Sanchez said. “In my community, District 14, we have a median income for a worker of $25,000 per year. That qualifies for nothing. Unless you give them a voucher, they qualify for nothing.”