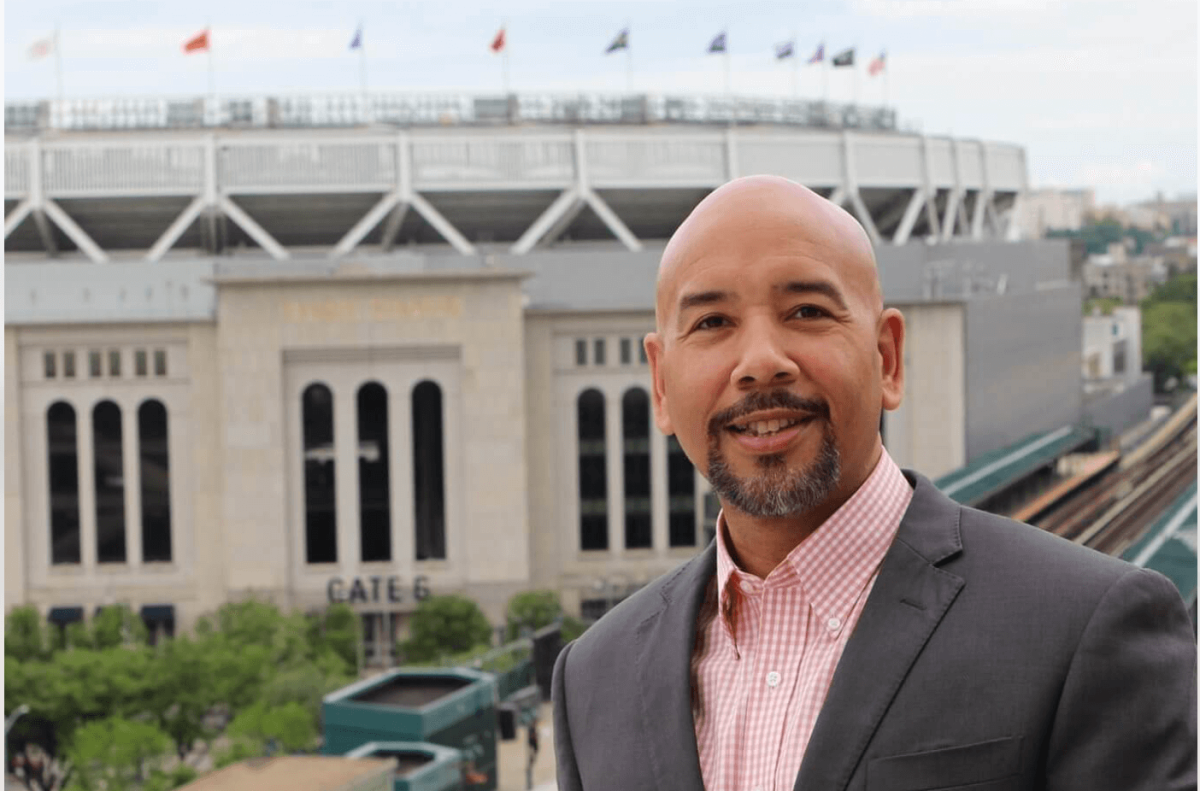

As his final days as Bronx borough president winded down, the Bronx Times sat with Ruben Diaz Jr. to talk about his life and legacy.

It seemed the next logical step for Ruben Diaz Jr. after a 12-year, three-term run as Bronx borough president was a promotion to Gracie Mansion. The prospect of becoming New York’s first-ever Latino and Bronx-born mayor was not lost on the 48-year-old Puerto Rican Soundview resident, who had been involved in New York politics since 1997, when at the age of 23 he became the youngest member of the New York State Assembly since Theodore Roosevelt.

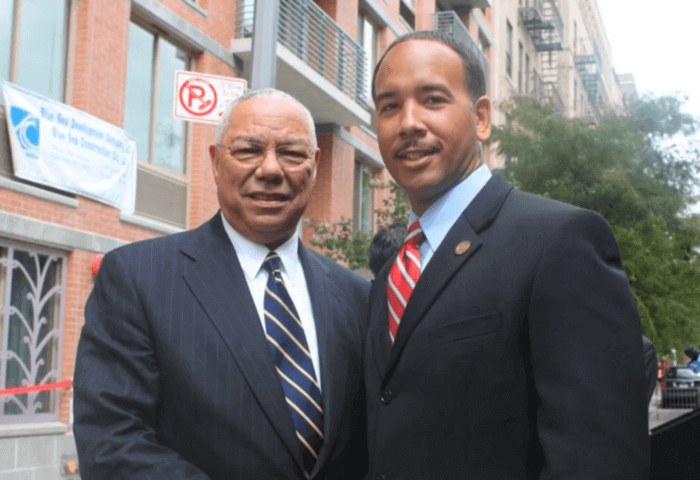

Diaz Jr., who went on to serve seven terms in the state Legislature, began making noise in Bronx politics as a charismatic progressive itching to change the status quo.

On the strength of the Rainbow Rebellion coalition – a rebel faction of the county’s Democratic party – Diaz Jr. became one of the faces of a changing-of-the-guard in the Bronx that led to the ousting of longtime party boss Jose Rivera, who had been accused of rampant cronyism within the party until being unseated in 2008.

In Diaz Jr.’s own words, if you can make it in Bronx politics, the rest of New York politics is manageable.

Diaz Jr.’s political rise – molded through lessons learned living in the Mott Haven projects – included a diverse cast of people he considers family, the very reason he withdrew his name for mayoral consideration in January 2020.

Diaz Jr., a proud family man, fondly remembers when he and his wife, Hilda, were two young 20-somethings raising their first child, Ruben III, in a rat-infested apartment on 156th Street.

“By the way, those were the best years of my life,” he recollects.

For Diaz Jr., the mayorship was a chance to show what a family born in the Bronx and bred by the Bronx could look like, how Hilda rose from a toll collector to assistant chief of operations at LaGuardia Airport.

He wanted to show off the young men and fathers that his sons Ruben III and Ryan, the latter a combat army guard who recently served in Germany, are becoming.

Diaz Jr. yearned to show the realities of his vibrant and blended family – Blacks, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans sharing love in one space – but his family wasn’t eager for the attention being the First Family of New York would bring.

“My family was like, we know you’re going to win and we know you’re going to put your blinders on, but we just don’t want to be in that bubble,” he said.

Without his family all in, Diaz Jr. wasn’t excited about a marathon campaign.

“I wasn’t going to go into this without my whole family’s support 100 percent,” he said. “I don’t mean ‘okay, go ahead do it,’ I mean I wanted to put my family out there to show the world what a Puerto Rican family from the Bronx really looks like.”

Like father, (un)like son

Diaz Jr. blazed a different cultural and political trail from his 78-year-old father, a socially-conservative Democrat and Pentecostal minister who isn’t known for evading controversy, especially when it comes to sharing his religious beliefs about gay marriage. A current member of the New York City Council, Rev. Ruben Diaz Sr., known for his trademark cowboy hat, announced he will retire from politics after the year ends, following a failed run for U.S. Congress in 2020.

Diaz Jr. mentioned marriage equality, abortion rights and handing out condoms in schools as topics they disagree on.

“I love my father,” the younger Diaz said. “I respect my father. I’ve never had an argument as an adult man with my father on anything personal, or private. All of the disagreements and the back and forth that we’ve had have always been around politics, policy and how we’ve been on opposite ends.”

In 2011, Diaz Jr.’s lesbian niece Erica Diaz, who was 22 at the time, held a counter-protest to a much larger anti-gay marriage rally Diaz Sr. held during an AIDS walk. But she ended up joining her grandfather on his stage, where they hugged in front of a crowd of people who didn’t believe she should have the right to marry. Diaz Sr., known as “Papa” in his family, announced he loves her and respects her decisions.

Erica’s move showed the crowd that while she disagrees with her grandfather, “nobody is going to stop the love that we have for each other as family members,” Diaz Jr. said, calling his niece “gangster.”

Diaz Jr. himself voted against gay marriage in 2007 while in the Assembly before changing his view after years of reflection, which he announced publicly in 2013.

In 2019, when Diaz Sr. got flack for saying the City Council is “controlled by the homosexual community,” Diaz Jr. tweeted that his father’s comments were “antagonistic, quarrelsome and wholly unnecessary.”

“What gets me so angry about my father is that he wants to create this public persona when it comes to issues like marriage equality, but that’s not really him,” Diaz Jr. told the Bronx Times. “And people think that this is who he is on [a] personal level, to the point that he doesn’t even get along with his granddaughter, his first grandchild. And that couldn’t be further from the truth.”

Diaz Sr. did not respond to requests for comment.

The two Diazes don’t completely veer from one another in the public sphere. The borough president said while “the list just goes on and on about where we differentiate,” they’ve worked together to bring services, jobs, housing and recreational activities to their constituents.

Diaz Sr. recently wrote a Dec. 16 op-ed in the New York Post criticizing Democrats’ bail reform efforts. He pointed to Alexis Dubouchet, 38, who allegedly stabbed Samuel Diaz, his supervisor at his NYCHA job – Diaz Jr.’s brother and Diaz Sr.’s son – in the back of his neck and twice in the head in the summer of 2020. The same suspect, who had 20 prior arrests and was let out on bail, allegedly shot and killed Anthony Rios, 38, the following summer while awaiting trial for Samuel Diaz’s case.

In 2019, Democrats in Albany passed legislation that ended cash bail for low-level crimes and misdemeanors, which has led to concerns over repeat offenders who can no longer be jailed – while awaiting court – based on the discretion of judges.

Diaz Jr. said while his father’s claim that the policy will turn Democratic Hispanic and Black voters Republican is political theatre, they are both frustrated with violent repeat criminals being romanticized under the guise of reform. “When we speak of reforming the system, we’re not talking about everybody,” Diaz Jr. said. “And people are getting frustrated. And a lot of the advocates who want to protect even the guy who attacked my brother are folks who don’t really feel that level of violence in their community, on their block. But for some of us, including my family, we’re not immune to that.”

Diaz’s record as beep

In Diaz Jr.’s 12-year run as Bronx beep, in which he first took office in 2009, he touted his brand of pragmatic progressivism as a means for rebuilding the borough’s image of crime and overseeing its gradual change in economic and infrastructural philosophy in the era of his predecessor Adolfo Carrion.

“I’m a pragmatic progressive,” he said. “And what does that mean? I know when to negotiate so that I believe something is better than nothing, and that’s lost in government and politics.”

The role of Bronx borough president — a ceremonial role that relies on its unique bully-pulpit position to affect sweeping policy rather than overt legislative authority — involves a dedication to NYC’s most racially diverse, yet often forgotten borough. Perhaps it’s no surprise the son of Puerto Rican immigrants who was raised in the ‘70s era of the Bronx – which was defined and marginalized for violent street crime and overpoliced, deprioritized neighborhoods — filled the position with a signature Bronx-born gusto.

In his own words, the lifelong Yankees fan “bleeds” the Bronx, which he wears as a badge of honor.

“I’m from the block and earlier in my career, some of my staff and family wanted to hide that fact,” said Diaz Jr., who finishes his third and final term on Jan. 1. “The thing is that on the block if I don’t like you, we don’t talk. … I learned that that wasn’t good governing and I had to adjust and put my best foot forward so that we can come together, plan out a strategy and execute it so that we can better serve the people that we represent.”

Diaz Jr. said he learned to be a more active listener debating in the Assembly and spoke of getting dinner with Republicans after debates on the floor.

But the camaraderie across party lines may not have translated back home.

Bronx GOP Chairman Mike Rendino told the Bronx Times he was disappointed the borough president didn’t reach across the aisle and claimed there were hardly any Republicans on community boards during Diaz Jr.’s tenure.

“Every time I see him it’s like I’m introducing myself for the first time, to be honest with you,” Rendino said. “It’s like I’m on the pay no mind list.”

But Diaz Jr. said he didn’t consider political affiliation in his appointments and is proud of the diversity on the boards.

The Diaz Jr. administration points to $23 billion in total investments throughout the borough, 117,000 new jobs, increases in housing stock — 55,295 residential units with roughly half government subsidized — and the gradual slashing of the borough’s unemployment rate to roughly 5% in February 2020 – compared to 14% when he first took office in 2009 – as major wins under his tenure.

He invested over $30 million of capital funds to a restoration of Orchard Beach, $3 million to create a sensory playground and $4.2 million in the Hip-Hop Museum as part of more than 1,000 projects he funded across $356 million from 2010-2021.

Diaz Jr.’s partnerships with developers also helped transform the Bronx. “When I got to Borough Hall, there were so many different plots of land owned by the city, in particular, that they would not develop,” he said.

But his vision didn’t happen without growing pains.

What was interpreted as a signal of gentrification, The New York Times listed the South Bronx among international destinations in 52 Places to go in 2017, suggesting artisanal coffee and linking to an article titled “South Bronx Gets High-End Coffee; Is Gentrification Next?”

Two years earlier, in November 2015, Diaz Jr. proclaimed on “The Brian Lehrer Show” that there hasn’t been any gentrification in the Bronx. “No one can prove to me that we forced one community out to bring another one in,” he said.

A South Bronx caller argued that Bronxites “are being pushed out daily,” to which Diaz called him misinformed, and said out of 17,000 units of housing he was part of over the last 6 years, the “overwhelming majority” was for low-income residents.

A month earlier, a billboard by Chetrit Group and Somerset Partners (headed by Keith Rubenstein, a Diaz donor) advertised planned Port Morris waterfront luxury apartments as part of The Piano District – an unsuccessful advertising and development effort that attempted to pay homage to the neighborhood’s history of piano manufacturing – drew pushback from residents fearing a rebranding of their neighborhood, and ultimately, gentrification.

During his Lehrer show appearance, Diaz Jr. – who was against the Piano District neighborhood label, albeit recognizing it was innocent – defended the proposed market-rate waterfront apartments, saying they would provide an opportunity for financially successful working-class Bronxites – who can’t afford to buy a house – to move out of low-income housing while staying in their own neighborhood.

While some argue there was too much development under Diaz Jr., others felt he missed a huge development opportunity at the city-owned Kingsbridge Armory, a giant building that has sat empty since 1996.

In 2009, Diaz Jr., along with local advocates, opposed a proposal to turn the armory into a shopping mall projected to bring 1,000 construction jobs and 1,200 permanent jobs. They wanted the developer to commit to a $10 an hour wage for mall employees, instead of the $7.25 minimum wage at the time. The City Council ultimately killed the deal over the low wages, then overrode former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s veto, who warned the building would remain empty for years.

In 2012, Diaz Jr. made lemonade out of that, going on to advocate for the Fair Wages for New Yorkers Act, requiring developers receiving $1 million from the city to pay employees a living wage.

The same year, he championed the building’s future as the proposed Kingsbridge National Ice Center, which would have become the world’s largest ice-skating facility. After financial woes and conflict with the city, the project never came to fruition.

“I got my butt kicked,” Diaz Jr. said of criticism over the building sitting empty.

But Diaz Jr. blamed the downfall on “ineptitude” from the developer, saying he didn’t capitalize while “all of the governmental and political stars aligned” in an unprecedented show of unity.

Even though the building remains empty, Diaz Jr. said his resistance to the mall was a watershed moment showing developers he wasn’t interested in short-changing Bronxites.

In the latter stages of his final term in office and despite his efforts, the COVID-19 pandemic began to unravel the economic progress scored under his administration.

A 2021 report from state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli showed that the pandemic stalled upward trends in population and economic growth in the Bronx leading to the borough’s ballooning 24.6% unemployment rate – the highest in NYC at that point – in May 2020.

Diaz Jr. said his duties as a leader changed with the pandemic. “COVID tested me, right,” he said. “If you look back on my Instagram page, while everybody was home, I was physically out in the streets. I was always getting [messages] from folks saying, ‘could you send some food to my grandmother?’”

From the hilliest part of the west Bronx to the flattest part of the east Bronx, Diaz still wishes he could’ve done more to help the 1.5 million New Yorkers who call the Bronx home.

“I’m not going to say [I’m] the least proud of anything, because I’m proud of it all, but, my biggest regret is not being able to help everyone,” he said. “COVID decimated us, and we’re still trying to get our arm around it.”

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. Reach Aliya Schneider at aschneider@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4597. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes.