With so few survivors left from the Holocaust, it is imperative that those who alive share their stories.

On April 26, the Bronx Women’s Bar Association held its 10th annual Holocaust Remembrance event, where Samuel Marder, author of “Devils Among Angels,” spoke about the perils of the shoah.

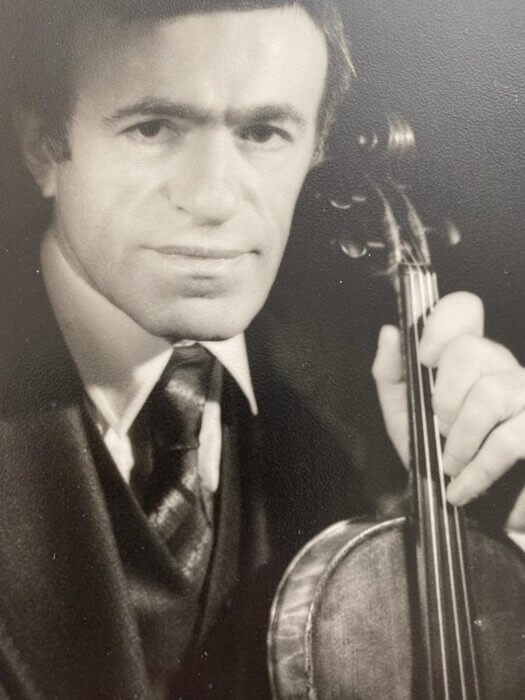

While Marder, 91, of Riverdale, is an accomplished and renowned musician, his path to success began decades ago but involves sadness, death, evil and murder.

“The journey was much longer; it would take many books,” Marder told the attendees.

Marder was born in 1930 in Chernovitz, Romania, now part of present-day Ukraine. His parents, Berl and Esther brought him and his sister Eva up in a religious home.

His dad owned a grocery store, so there was always food on the table.

“My life as a child was normal,” Marder recalled. “I had a loving father and mother. He always wanted to do everything that was best for us.”

At age 4, he entered a private Jewish school and two years later began taking violin lessons. Marder did not like his teacher, but eventually went to a local conservatory, and at age 10, won a prize, which made him eligible to study at the Moscow Conservatory. He never went to Moscow, because it was so far from home.

Marder recalled his first experience with anti-Semitism was at school when kids threw rocks at him.

“I was shocked,” he said. “I didn’t expect anything like that.”

Then the war began.

According to Marder, word came from Vienna, Austria that Germans were shooting and beating Jews, but his father did not believe it.

“My father said it wasn’t possible because the Germans are a cultured people,” he commented.

The Nazis took over Czernowitz and life was turned upside down. Thousands of Jews were killed in the first days. A ghetto was built and the Marder family was deported to a Nazi concentration camp in Transnistria (Ukraine).

They traveled part of the distance in closed cattle cars where many died and the rest by foot, where more perished as well. Then the Nazis forced them to walk for days and anyone that lagged behind was shot.

“It was so painful I forgot I was hungry, thirsty and cold,” Marder said.

At 10, his family was living in a ghetto surrounded by barb wire. The conditions were horrid and they could only go in the street during certain hours for food.

“We were like sardines, we could only lie down on the floor,” Marder recalled.

Berl always tried to keep a positive outlook and never thought things could be as bad as they were.

“My father tried to still be in his good mood,” Marder said. “Maybe they are bringing us here to do some agricultural work he thought. Soon we found out the real truth.”

The family spent 3 1/2 years in Transnistria, where Berl died from typhoid and starvation.

While in the ghetto, Jews were summarily executed, and Marder constantly heard bullets flying.

Eventually, Marder, his mother and sister, made it to Fohrenwald, a Displaced Person’s Camp in western Germany.

With a gun to his chest, Marder lied and told a Nazi he was Ukrainian. In fact, it was there where a Nazi taught him the violin.

At 19 they arrived in America and for the first time he felt safe.

Marder continued his musical studies at the Manhattan School of Music, obtaining his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, followed by post graduate studies at Teacher’s College, Columbia University.

From there, he toured throughout the country and worldwide.

He has retired from playing the violin and his passion is speaking about the Holocaust. For the past 20 years, Marder has talked to children about his experience.

“Whether I talk to children, teens or adults the results are satisfaction when I see that I can help them increase awareness in the importance of kindness in human relations and the horrific dangers of prejudice,” he told the Bronx Times. “It feels that I am doing something good when I can make use of my experiences to help people realize the frightening results of indifference.”

Marder noted that a common question he is asked is if he still has faith in God.

“Yes, I believe in God who is spirit beyond the capability of the human brain to comprehend,” he said.