Directly adjacent to P.S. 51 Bronx STEM & Arts Academy, a school in the Bronx’s Belmont neighborhood, sits a modestly-sized gymnasium with a domed, brick exterior. The outside displays various hues of crimson red, the inside colored in shades of blue and yellow. Across the middle of the floor a net stands regulation height, as girls pull on their knee pads and lace up their court shoes in the corner.

The girls play for Legacy Volleyball Club — a 501c(3) in the Bronx that aims to promote the sport to young athletes with year-round programming, and one of 12 NYC recipients of a new Nike program that awards grants to clubs that encourage young girls, especially young girls of color, to participate in sports.

Nike launched the Made to Play program in conjunction with the NYC branch of Laureus Sport for Good — an international athletic organization that aims to use sport as a tool to help children overcome violence, discrimination and disadvantage in their lives. The grant offers clubs a three-year, $1 million commitment.

Matt Geschke, the senior director for North America social and community impact at Nike, told the Bronx Times in a December interview that the Made to Play grant campaign’s purpose is to move the world forward through the power of sport. But more specifically, by catering to young girls in historically underserved areas.

“We know that only one in five kids get the physical activity they need to thrive, and that girls and kids from these undervalued communities are moving the least,” Geschke said.

Data from the University of Minnesota’s Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport shows a clear gender gap in athletics. In the 2009-2010 school year, there were 53 athletic opportunities offered for every 100 high school boys — compared to 41 for every 100 girls. During that same academic year, high schools offered an average of 15.9 teams for boys and only 14.3 for girls.

Research suggests that there could be a direct correlation between athletic opportunities for women and girls and their retention rates.

“We do know that girls are dropping out of sport at two times the rate of boys, and we also know that when girls hit the age of 10 they’re two years behind boys on physical literacy skills,” Geschke said.

Between eighth and 12th grade, Tucker Center data shows that about 32 of every 100 athletes dropped out of sports, but girls were two to three times more likely.

Geschke said representation of women and girls in sports can be addressed through a wide range of creative programming — from recruiting more women coaches to reflect the populations they serve, to creating a positive experience for girls when they get their first sports bra.

The data makes it clear that athletic organizations and programs need to not only rethink their approach to girls in sport, he said, but reframe the culture surrounding women in athletics altogether.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all, and I think sport has traditionally been designed that way,” Geschke said. “We want to make sure that we’re designing with intent and purpose, for her.”

On the court

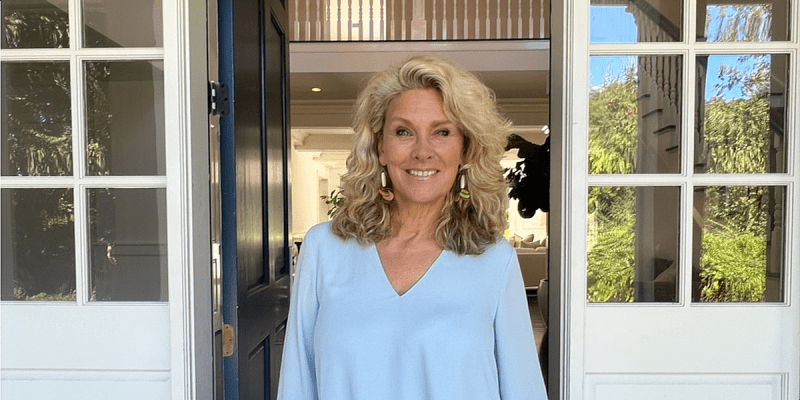

Edeana Martinez walked into the gym at P.S. 51 just before practice started on Dec. 12, 2022, the purple Legacy logo on her tee shirt matching the volleyball under her arm.

As the coach of the Legacy Volleyball Club — which is free to all athletes — she said she strives to be a source of structure and discipline for her girls, as well as provide a place they can come to get out of the house.

Martinez played soccer, basketball and ran track in high school, but she actually didn’t even pick up volleyball until college. She said the people she has met playing and coaching have kept her involved in the sport all these years.

“There’s something about the volleyball community, everyone is just very open, accepting, welcoming,” she said.

The girls — ages 14 and 15 — worked on their serving, passing and hitting during their practice in Belmont.

Gabriela Pilarte, Nicole Bennett and Heidy Jiminez, all high school sophomores who play with Legacy, told the Bronx Times after their session that volleyball is much more than just an hour a few times per week in the gym. The girls said it’s a motivator to keep their grades up, a way to stay in shape, but most importantly — a place where they can let everything else go.

“Everytime I play volleyball, it’s just my safe space. I can be me,” Bennett said. “As soon as I step on the court and go to play, everything’s gone — all the stress is gone.”

Jiminez, who joined the team this year, said volleyball makes her feel more confident.

“It made me come out of my shell a lot,” she said. “I remember I was really shy and introverted and now after I joined the team they made me feel safe, and they made me feel comfortable to open up.”

And when it comes to the difference in culture surrounding girls and boys in high school sports, the Legacy players said it’s sort of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they said women’s volleyball seems to attract more fans than men’s volleyball. But on the other hand, sometimes the sport is viewed as “light,” or not as physically demanding.

Pilarte said she still sees antiquated ideas about women’s roles present in volleyball. When boys make mistakes people know “he’ll get it the next time,” she said, but when a female player makes a mistake she’ll get pretty down.

“The world has put in their head that they have to look and act a certain way when that’s not the case,” Pilarte said.

Across the city, in East New York, Brooklyn, another group of young girls is benefitting from the Nike Made to Play program. They pride themselves on being more than a team — they’re a sisterhood.

“As I was coaching, I started to notice that there were major gaps between major transitional periods for young girls playing basketball,” said Chiené Joy Jones, the founder and head coach of the Grow Our Game hoops nonprofit in Brooklyn. “The mission for Grow Our Game is really simple: It is to empower young girls to become fierce, amazing leaders through passion, confidence and sisterhood — all while learning the game of basketball.”

Jones said she became hooked on the game when she was in fourth and fifth grade, after accompanying an elementary school friend to a basketball tryout. Her first coach was a woman, which she said instilled that sense of power and camaraderie in her at a young age. Since then she’s always remained active in the sport — playing basketball for New York University, and now as a referee, coach and program founder.

“It was truly the sisterhood that sparked my interest,” she said. “I think that sisterhood is a bigger piece that many people actually forget along this journey.”

The Grow Our Game team, which is also free for all participants, is made up of girls from different age groups and experience levels.

Nicole Gladden’s youngest daughter — Ari-Joi, just 3 years old — practices with the older kids. She said the program is one of the few in the area that is specifically designed for girls.

“For such a long time girls were always put on the back burner, as if we weren’t good enough or as good as,” Gladden said during her daughter’s practice. “Now with programs like this we’re showing our young girls … it’s OK to want to be a basketball player, it’s OK to want to be better than your counterparts.”

She said her youngster comes from an athletic family — Gladden herself played basketball when she was younger, her husband is a hoops coach, and her older daughter plays basketball and soccer, and also runs track and swims.

Grow Our Game, Gladden said, “is so much more than just basketball.” Coach Jones’ talks, welcoming circle and trademarked Sisterhood Affirmations — where the girls tell themselves and each other that they are strong, smart, beautiful and all capable after every practice — are all part of the bigger picture, she said.

“She is instilling in them the confidence and just a ‘we can do it’ attitude,” Gladden said. “As a parent, I love seeing it.”

‘Rounding up a new tribe’

The girls who play for Grow Our Game and Legacy come from mixed backgrounds. Martinez said many of her volleyball players come from either single parent homes or working-class dual-parent families across the South Bronx, Harlem and Westchester County. Jones said her hoopers are diverse in family dynamic, some of whom are growing up in “major pockets of poverty.”

According to data from the NYU Furman Center, the poverty rate in the Belmont and East Tremont section — where the Legacy Volleyball Club practices — was 40.3% in 2019, compared to the citywide average of 16%. And in East New York and Starrett City, Brooklyn, it was 23.3%, also higher than the citywide average.

Martinez said one of the most important parts of coaching is representation. Born in Belize but raised in the Fordham and Pelham Parkway section, she said didn’t see very many women of color like her playing volleyball when she was growing up.

“For young girls, I think that it’s great for them to see other females like themselves,” Martinez said. “And just to know that it’s a possibility for them to do whatever it is that they want.”

In the Belmont and East Tremont neighborhood, 58.9% of residents identified as Hispanic and 36.1% identified as Black in 2019, according to the Furman Center. In the same year, 55.4% of East New York and Starrett City residents identified as Black and 34.9% as Hispanic.

Peter Feldman, the director of programs at Laureus — the NYC nonprofit partnering with Nike for the Made to Play campaign — said representatives from various grant recipients meet regularly to discuss how to make programs more equitable.

“We’ve been kind of exploring … how can organizations better support female coaches, particularly female coaches of color,” he said.

To identify areas of investment, Laureus analyzes data about youth movement and athletic retention, Feldman said. But also, statistics on unemployment, poverty, incarceration rates, as well as other health outcomes — like asthma — and how they impact communities, all played a role in the grant initiative.

Jones, the founder and coach of Grow Our Game, said sports have the power to lay the foundation for young girls to break some of these institutional barriers.

According to data from the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program, athletic activity helps children develop and improve cognitive skills. Research also shows that high school athletes are more likely than non-athletes to attend college and get advanced degrees, and a survey of 400 female corporate executives found that 94% of them played a sport.

“The bigger piece that many times we’re missing is the incredible opportunity that sports has for young girls of color within underserved communities — to use that as a catalyst to then break generational poverty,” Jones said. “So as a result of being able to have all of these amazing transferable skills, your likelihood of finishing high school increases exponentially, the likeness of you going to college and finishing college increases exponentially.”

Grow Our Game and Legacy Volleyball, along with the 10 others that received Made to Play grants, are sports clubs, first and foremost. But, Jones said, these organizations are actually carving a path for a new generation.

“When we’re providing resources that don’t even exist in these communities, we’re actually rounding up a new tribe of successful young people that ultimately is going to shatter statistics, but more so than anything else, creates safer spaces within the community,” she said. “We’re like a small fingerprint on a young girl’s trajectory in life, but we want this opportunity to be a positive one.”

Reach Camille Botello at cbotello@schnepsmedia.com. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes