At the southernmost end of Alexander Avenue just across the Harlem River from Manhattan sits an independent school that has been teaching the Bronx’s youth about the power of storytelling for nearly a quarter century now.

The Ghetto Film School in Mott Haven is by no means distasteful as its name, taken literally, implies. It’s actually quite the opposite.

Located on the fourth floor of one of the sector’s old piano factories, the facility is complemented with hardwood flooring, aged brick painted white and natural light seeping through its many oversized windows. From the conference room, decorated with a simple elegance (just one long table, chairs, a whiteboard and a piano) one can see a mural bearing the borough’s name atop a nearby building.

But while the school teaches its students about the power of story, the story of the school itself continues to be heralded by people from every corner of New York City, and all around the world.

The school finds a home in Mott Haven

The nonprofit Ghetto Film School was founded in 2000 by Bronx social worker Joe Hall, and has since opened locations in Los Angeles (2014) and London (2020).

Just before the school’s inception in 2000, Hall had returned from a stint at the University of Southern California’s graduate film program.

According to a 2007 feature in the New York Times, Hall “quickly became disillusioned” during his time studying at USC — almost all the students in the film program were “white and wealthy, and most had family connections to the movie business,” a world unlike the one he knew working at home in the South Bronx.

In the early 2000s, Mott Haven looked a little different than it does now, although many defining characteristics remain the same.

The neighborhood, basically located as south in the South Bronx as one can get, like the rest of the borough was reeling from decades of hardship before the Ghetto Film School was founded — including displacement after the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway in the 1950s, and frequent structural fires in the 1970s that inspired national buzz that “the Bronx is burning.” Mott Haven was hit particularly hard with disinvestment in the following years — described as a neighborhood “left behind” the rest of the South Bronx in a 1994 New York Times piece, where “the ravages of crime and drugs and decay have continued unabated.”

According to the Mott Haven oral history project, the South Bronx’s “story of decline, suffering, and abandonment makes an irresistible backdrop for a story of rebirth.” Residents started to be credited globally for their unapologetically Bronx-inspired contributions to popular culture — through art like hip-hop, graffiti and breakdancing, to name just a few.

But this story of rebirth, as the oral history project calls it, is complicated.

As one of New York City’s last untapped waterfront communities, Mott Haven has faced a boom in development in recent years — which some worry will further gentrify the neighborhood.

“Will we be priced out of here in a few years or will that new development trickle down to the community?” longtime Mott Haven resident Samia Taylor said in an interview with the Bronx Times last year. “You always wonder who’s going to be able to afford these properties in a few years and if you gotta start looking over your shoulder for who’s changing the neighborhood.”

Hall has asserted that the name of the film school encapsulates some of the history of the area — but in an ironic way, reclaiming what people have always uttered about the South Bronx.

During the school’s beginning stages, neighborhood teens told Hall they didn’t want a school people would abhor, or pity. They wanted to be taken seriously.

“One said, ‘I don’t want to come into a place and find out someone is trying to raise my self-esteem,’” Hall told the New York Times in 2007. “Another said, ‘Yeah, it’s not like we want a ghetto film school.’ Everyone started laughing, and I thought, ‘What if we could co-opt a negative term and throw it back out there, do the exact opposite?’”

An educational model to tear down ‘invisible ghetto walls’

Today, parts of Mott Haven are starting to resemble other trendy NYC sectors (the area was even called one of the city’s new “it” neighborhoods by Crain’s New York earlier this year). The block off Alexander Avenue where the Ghetto Film School is located is bursting with brightly colored storefronts and murals — many of them motifs for the legacy of resilience of the South Bronx — and construction can often be seen along the Harlem River.

Students of the film school could see both the art and the construction from their classroom windows on Aug. 21, during the last week of their summer 101 course. Kids sat with their laptops — some in groups, some alone, some at desks and others in the editing suite — working on their final non-dialogue short films.

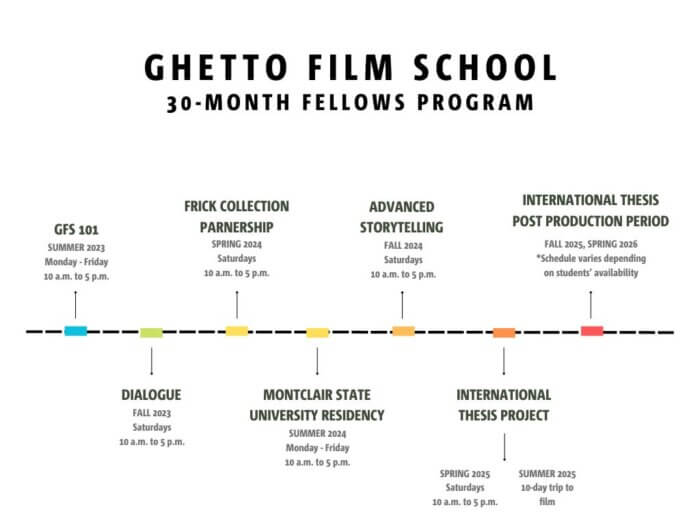

The school’s Fellows Program is a free 30 month-curriculum students complete while attending their individual high schools. The program, which mostly draws students from the Bronx and upper Manhattan, starts with the summer 101 course and concludes more than two years later with an international thesis project — where students travel to a foreign country (upperclassmen were on their way back from the Dominican Republic as 101 wrapped up last week) to shoot a film in that nation’s home language. The cap for each incoming class is 35 students.

The summer introductory session, a kind of crash course into the film industry, basically requires students to dedicate the same amount of hours they would to a full-time job. For the next two-plus years, Ghetto Film School students are working on their film curriculum on Saturdays during the regular school year, and summers when school is out. The film school also aims to remove as many socio-economic barriers for students as possible — so along with free tuition, the school also gives the kids MetroCards and free lunch.

In its final semesters, the Ghetto Film School contracts academic counselors to help kids apply for both college admission and financial aid, boasting a 95% matriculation rate for its students. The school also has an extensive network of alumni, in what’s called the Roster Program, who the Ghetto Film School connects to its industry contacts for collaborative work after they’ve completed the 30-month Fellows Program.

Many Ghetto Film School alumni go on to work professionally in the business, some starting their own film companies and others signing on to work on campaigns with big-time partnership corporations like Netflix and Red Bull.

Last October, because of the school’s industry connections, students were paid a visit by “Everything Everywhere All at Once” directors Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (known as “the Daniels”), as well as the movie’s producer Jonathan Wang and Stephanie Hsu, the actress who plays “Jobu Tupaki.” The film won roughly three dozen accolades for its acting, production and writing, including the 2023 Academy Award for Best Picture and the 2023 Academy Award for Best Directing.

But while the Ghetto Film School is a highly sought-after program for aspiring filmmakers, Executive Director John Mernacaj — who took the position in 2021 — said the students don’t actually need any experience before they enroll. He’s just looking for kids with a knack for the art of the story.

“We’re not looking for people who know how to hold a camera or frame a photo or anything like that,” he said. “If you have a story you want to tell, great. We’ll help you make it.”

There wasn’t a single moment that ignited Mernacaj’s curiosity for filmmaking. The son of Albanian immigrants, he said it just came from watching lots of TV and movies as a kid in his childhood home in Wakefield.

“I remember we didn’t have a camera growing up so I used to use a laptop webcam to record things,” the 27-year-old said. “Me and my siblings used to play around and just make some things together growing up when we were really young.”

In his high school years, Mernacaj attended the city Department of Education’s (DOE) Cinema School in Soundview, which was founded by the Ghetto Film School in partnership with the DOE. During his gap year and throughout college he kept in touch with the Ghetto Film School, taking different jobs there on-and-off for years.

“One winter I was helping them establish the back space, knocking down walls and helping them vision out what it looks like … which was actually a fun job,” Mernacaj recalled. “The only frustrating part was lugging down hundreds of pounds of sheet rock, but that’s a whole other story.”

Jacob Stebel, the Ghetto Film School’s program director, is also from the Cinema School. But he wasn’t a student, he was actually one of Mernacaj’s teachers there.

“He became executive director here, he asked and I could not say ‘no’ to him,” Stebel said about leaving the DOE and joining the Ghetto Film School full time last year. “This place is so special and I’ve seen what this does for my former students.”

Alex Osei was hard at work on his non-dialogue film before 101 wrapped last week. The 15-year-old said his first summer session has been both the most stressful time in his life, and the best.

“It’s like a rollercoaster in a way, when you’re on it you’re scared and fearful but when you’re off of it you miss that feeling, you miss that rush,” Osei said.

He told the Bronx Times he decided to dedicate his life to artistic activism earlier this year, and he sees the Ghetto Film School as a vehicle for that path. An incoming sophomore at Cardinal Hayes High School on the Grand Concourse, Osei will next dedicate all his Saturdays to his film endeavors during the school year.

“I knew that’s what I wanted to do in life — make art that said something, that showed my beliefs and showed my views,” Osei said.

Stebel said he not only hopes to bring up the next generation of filmmakers like Osei, but also serve as an educational model.

“We really want them to go into the industry understanding story is the heart of everything, there’s no value without valuing story,” he said.

The Ghetto Film School is on the cusp of its 25th anniversary (just over a year away), which has been an inflection point for upper management. While working to manage classes and submit last year’s Icelandic international thesis project to film festivals, the school’s leadership is also thinking about what’s to come in the next quarter century.

“It started as a small operation, a summer program, and it grew very quickly,” Mernacaj said. “What we’re looking to do as we approach our 25th anniversary is really grow that scale and capacity in terms of our impact.”

The institution, a 501(c)3, is already slated to receive $110,000 from the New York City Council in Fiscal Year 2024 — $75,000 courtesy of Speaker Adrienne Adams and the remaining $35,000 in discretionary funds from Bronx Councilmembers Rafael Salamanca, Amanda Farías and Diana Ayala.

At some point in the next few months the school is also planning to launch a new capital fundraising campaign, with the intention of investing more into both the Fellows and Roster programs, as well as the staff — which rotates because many of them are full-time filmmakers themselves. With other locations in Los Angeles and London already, the Ghetto Film School is also looking to expand into other cities — whether that’s by opening other locations or partnering with other schools.

But after everything gets boiled down — what this money funds, Ghetto Film School staff say, is something invaluable.

“Despite the changes in academy award winning eligibility, there still are invisible ghetto walls around Hollywood that are keeping Black and brown people out and we exist to be a pipeline to industry,” Stebel said.

Reach Camille Botello at cbotello@schnepsmedia.com. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes