On Sept. 11, 2001, 2,996 people lost their lives in what remains the single-deadliest terrorist attack in human history.

Roughly 3,000 names are adorned on the bronze wall of the 9/11 Memorial & Museum that is located at 180 Greenwich St., two blocks from where the Twin Towers fell 20 years ago Saturday.

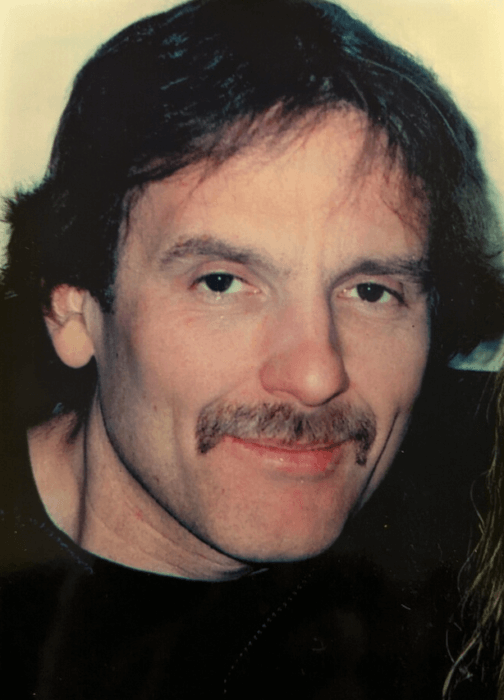

On that bronze wall is the name of Danielle Kelly’s father, Maurice Patrick Kelly, a “providing, fun-loving and amazing” father who was gone at just 41.

Danielle Kelly, 37, was a junior at Mamaroneck High School on Sept. 11, 2001, and said her father, a carpenter, was patching a ceiling for Cantor Fitzgerald on the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center.

But Maurice Kelly, who was living on City Island at the time, wasn’t originally supposed to be there that morning.

“He got called in randomly that day,” she told the Bronx Times. “I remember that [school] day, I had a break and everyone was crowding around the TVs in the classrooms and they showed the plane going into the building and I didn’t know what was going on.”

At the time of the morning attacks, Danielle Kelly was unaware that her father had been in the North Tower.

But after several unanswered calls to Maurice Kelly’s normally responsive beeper and no communication in the following half-hour, Danielle Kelly said there was a looming sense that her father had passed.

“He would pretty much call back in a half-hour tops, so when he didn’t, I had a weird feeling he was gone,” she said. “There were no calls and all they had found was just a card with his name on it. So at that moment, a big piece of life was gone.”

There were an estimated 3,051 children, according to Terry Sears, president of the nonprofit Tuesday’s Children that lost a parent on the day of Sept. 11. Tuesday’s Children was founded in the wake of 9/11 to support children and families who lost a loved one on 9/11 and has expanded its scope over the years to support those who have lost loved ones due to military service, mass violence or acts of terrorism.

There is also another population of those personally affected by the 9/11 attacks that have been in search of answers and closure for decades.

In the 20-year aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, there are still an estimated 1,110 victims, roughly 40% of those who died on 9/11, that remain unidentified.

Morgan Laird said that her fiancee Ben Johnson was in the North Tower working on the 98th floor when the California-bound American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston’s Logan Airport crashed into it.

Laird, 58, said she had been at home when a breaking news report on the local Boston channel 2 news had shown the plane crashing into the North Tower.

“My body immediately went cold and I just remember seeing a plane crash into one of the Towers, and I kept saying to myself that maybe Ben had been late to work or maybe he was out on a coffee run,” she said. “But when you frantically call and call and call, and get no answer, this sick feeling consumes you.”

Laird would frequently visit Johnson, a Queens native from her hometown in Newton, Massachusetts, with plans to move to New York City the following spring.

Laird said that when she found out the details surrounding the attack — Flight 11 had been hijacked by Mohamed Atta, a key mastermind of the 9/11 attacks — she didn’t know how long it would take for her to receive confirmation of his death or identification of his remains.

Any hope for closure for Laird might lie through new forensic technology that recently identified two more 9/11 victims.

Dorothy Morgan of Hempstead, New York, was the 1,646th victim to be identified through ongoing DNA analysis of unidentified remains recovered from the 9/11 disaster. The second person — and the 1,647th victim — is a man whose name is being withheld at his family’s request.

The new technology is courtesy of the New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner. It marks the first time in two years a victim’s remains have been identified.

According to The New York Times, forensic scientists are testing and retesting more than 22,000 body parts that were recovered from the World Trade Center site.

Laird said that while she’s been in contact with forensic scientists in New York about possible identification of Ben’s remains, she feels closure for the loved ones of the victims of 9/11 is seldom.

“We’re still waiting and I don’t think that day will ever come,” Laird said. “I still have some pieces of him with me. The wedding ring, a few ‘I love you cards,’ but I think like most people who lost someone on that date, you truly never get closure or peace.”

Danielle Kelly said that each subsequent Sept. 11 got “harder and harder” and when she visited Ground Zero memorial in 2002, seeing her father’s name memorialized, hit close to home.

“Personally, it felt unbelievable, that he was here one day and not the next, and it seems like a surreal event,” she said. “Seeing his name definitely hit home more, it’s more heartfelt, and whenever you see something that reminds you of that person, you remember all memories you shared and milestones missed.”

Kelly said that trips to Ground Zero, a site that would then become One World Trade Center, had been frequent until it wasn’t, as a mixture of trauma and the next 20 years of school and work milestones took place.

In 2019, for the first time, Kelly took part in the annual commemorative reading of the victim’s name, an experience that she said, “took a while” to gather the strength to endure.

The tradition will once again resume after the name-reading portion of the program was canceled in 2020 to keep participants from gathering in small crowds during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I did it when I finally felt I had the courage to do so, and it took a while for me to get to that point,” she said. “I’m glad I was able to do it. It’s never easy with each Sept. 11, but you do have time where you remember how special that person was to you and how important each year since the day becomes.”