During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic’s pause on in-person activities, feelings of depression and isolation among individuals with Alzheimer’s disease rose and advocates and medical experts say the adverse mental health effects caused deaths related to the neurological disorder to increase by approximately 17% more than expected.

Alzheimer’s is the only cause of death among the top 10 leading causes of death that cannot be prevented, cured, or even slowed.

Concurrently, caregivers, who described the duty of caring for Alzheimer’s patients as a 24/7 job, felt a high rate of burnout. In a May survey conducted by UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, 25% of dementia and Alzheimer’s caregivers said physical or mental changes related to the pandemic — as well as feelings of isolation — affected their ability to care for themselves and their loved ones

One of the main reasons for accelerated burnout among caregivers was the closure of adult day care and respite care services during the pandemic, which also give individuals impacted by the disease essential activity and therapeutic programming.

Two Bronx caregivers told the Bronx Times they considered quitting during the pandemic because of the high stress of the caregiving role and deepened frustration felt by those affected by the disease.

Caregivers provided 15.3 billion hours of unpaid care in 2020, valued at almost $257 billion, to people living with Alzheimer’s and other dementias. And with that came a heavy toll on their mental health — where prevalence of depression is higher among dementia caregivers (30%-40%) than other caregivers, according to the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America.

“Isolation is a major challenge faced by families affected by Alzheimer’s — it can accelerate the disease progression and contribute to caregiver burnout. COVID-19 significantly added to this challenge,” said Sandy Silverstein, spokesperson for the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America. “Many care settings closed their doors to outside visitors to protect their residents’ health and safety, but this prevented families from being able to see and hold their loved ones.”

For the first time in two years, families affected by the disease — a cerebral condition that slowly deteriorates cognitive function over time — and their caregivers will convene in Manhattan on Wednesday to attend the educational conference held by Alzheimer’s Foundation of America.

Conference officials told the Bronx Times that the event — which starts at 8:30 a.m. at Midtown’s Harvard Club — will include guest speakers who specialize in dementia care, caregiving and elder law. Additionally, free memory screenings will be available at the conference, and perhaps most importantly, a sense of community for families and caregivers.

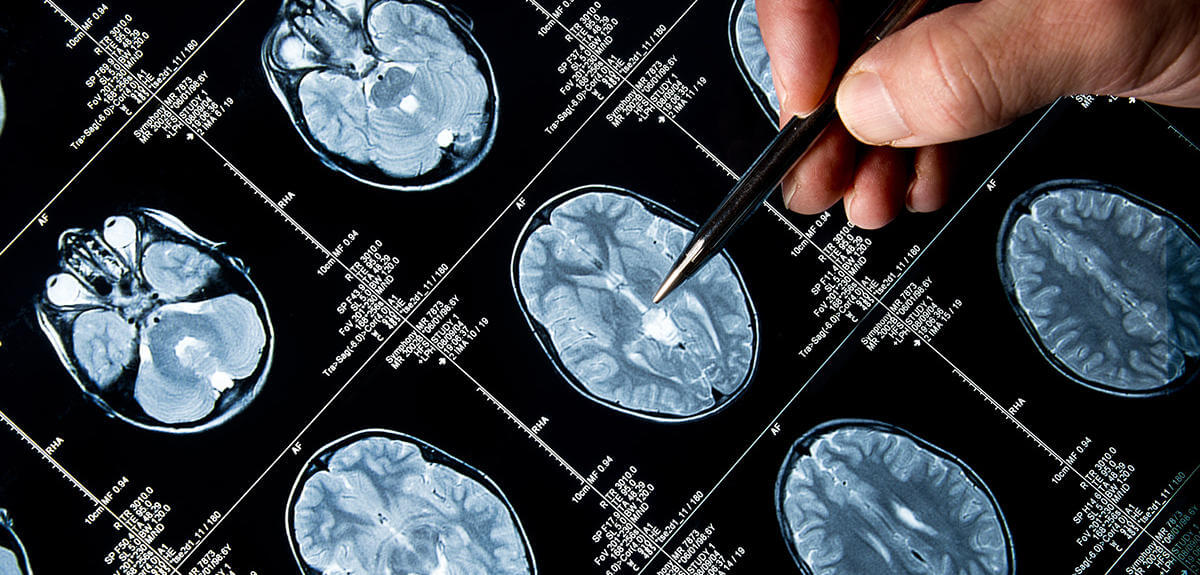

An estimated 410,000 New York state residents have some form of Alzheimer’s disease, and that number is expected to increase to 460,000 by 2025, according a recent study from the Alzheimer’s Foundation. Alzheimer’s is a fatal disease, and symptoms usually start when a person has difficulty remembering new information. In advanced stages, symptoms include confusion, mood and behavior changes, and an inability to care for one’s self and perform basic life tasks.

The risk and prevalence of Alzheimer’s is heightened among Blacks and Latinos — data from the Chicago Health and Aging Project [CHAP] study showed that 18.6% of Blacks and 14% of Hispanics age 65 and older have Alzheimer’s compared with 10% of white adults of the same age demographic.

By 2030, CHAP data suggests 40% of Alzheimer’s patients in the U.S. will be Latino or Black. According to UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, someone in the United States develops Alzheimer’s every 60 seconds. By 2050 this is projected to be every 33 seconds.

Positive developments have been made in disease research and possible cure sourcing, however.

Federal funding for Alzheimer’s research has increased from $500 million a year in 2012 to $3.4 billion in this current fiscal year

“Building on this progress is essential in the years ahead so that we can continue to advance the science and hopefully find the cure or treatment for which all of us are hoping,” said Silverstein. “We are still working toward finding a treatment and cure, as well as some of the underlying causes of Alzheimer’s.”

Last year the drug Aduhelm, which was developed by U.S. pharmaceutical Biogen, received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), making it the first Alzheimer’s disease medication approved by the FDA since 2003.

However, the two advanced drug trials for Aduhelm yielded contradictory results. Biogen’s data failed to prove the drug can slow down cognitive decline in patients, which has led to skepticism on its widespread usage and potential as a cure for the disease.

Despite those concerns regarding the clinical trials, the FDA has authorized Aduhelm for accelerated approval in June 2021.

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes