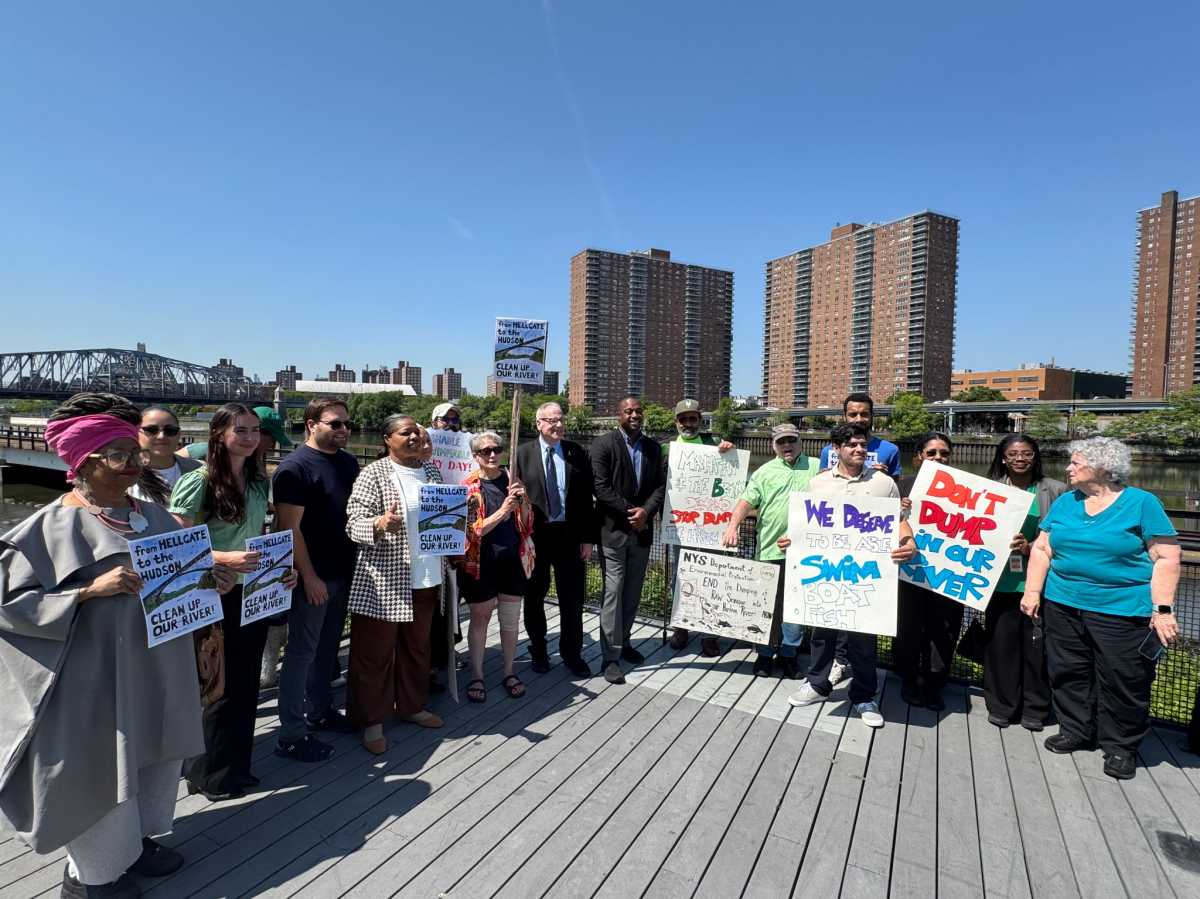

Bronx clean water advocates sounded the alarm Tuesday at a press conference in Mill Pond Park over a state proposal that would exempt the Harlem River from meeting certain clean water standards—effectively locking in poor water quality for decades to come.

Advocates accused the state of shirking its responsibility to clean up the river, choosing instead to seek a regulatory workaround that would spare it from making costly improvements.

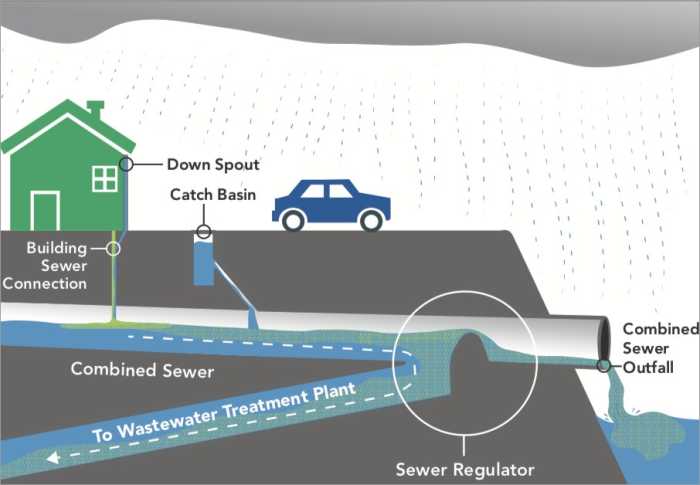

The proposed exemption would allow an estimated 1.9 billion gallons of sewage and polluted stormwater to continue entering the Harlem River each year. These discharges occur during even moderate rainfall, when the borough’s outdated combined sewer system overflows and dumps untreated waste into the waterway.

The event, which drew clean water advocates from both Manhattan and the Bronx, centered on a proposed water quality reclassification by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) that would exempt it from having to improve the infrastructure in order to meet a higher standard. Under the proposal, the Harlem River would be designated as a “wet weather limited use” (WW) waterbody, meaning that for 36 hours during and immediately after it rains, the state would suspend the required water quality standards which would make the river safe for swimming boating and fishing.

The Harlem River, a tidal strait separating Manhattan and the Bronx, is one of the most polluted waterways in New York State, primarily due to Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), a type of pollution common when both storm water and sewer water share a single sewage system.

“To me, this is not a liberal issue or a conservative issue, a Democrat or Republican issue, this is a commonsense issue,” said Assembly Member Landon Dais at the press conference, who represents a large swathe of the borough along the river.

The assembly member paused to excuse his language before adding, “We don’t want that crap in our water.”

The DEC justified its decision to suspend higher water quality standards in an April report. The agency argued that it would be too costly to improve the Harlem River’s water quality and that an overhaul of the sewage infrastructure was not financially feasible.

Critics at the rally slammed this rationale as an all-or-nothing approach resulting in inequality for the Bronx. Em Ruby from the river protection program Bronx Riverkeeper, suggested smaller, more cost-effective solutions and green infrastructure to reduce the pollution in the Harlem River without having to invest in a new sewage system.

“ We know that the city and the state can take incremental actions over a series of years and set the goal high,” Ruby said.

Local leaders emphasized the environmental justice dimensions of the issue. The Harlem River borders neighborhoods that have historically faced systemic disinvestment and limited access to waterfront spaces.

“This is an environmental justice issue, a racial justice issue, and a health justice issue,” said longtime community advocate Chauncey Young. “The Bronx is 62 out of 62 counties in the state of New York in terms of health disparities.”

Young said that committing to a clean Harlem River would allow much-needed opportunities for outdoor recreational activities that keep Bronx residents active, healthy and in shape.

Rowers and community recreation leaders echoed those concerns. Joy Hecht, a local rowing enthusiast with Harlem River Community Rowing, described the health risks rowers face every time they use the river—often without any notice of sewage overflows.

“We like to be on the water,” Hecht said. “We try not to be in the water, but it sometimes happens. We get wet, we get splashed by boats that put out mammoth wakes.”

Support also came from U.S. Representative Ritchie Torres and State Senator José Serrano, who both sent representatives to rally, read statements opposing the reclassification and calling for continued investment in water quality improvements.

“Any proposal that weakens protection for our river is an affront to the health, dignity and future of our community,” Torres’s statement said.

As chants of “Don’t dump in our river” and “Clean up Harlem River” rang out across the park’s waterfront lookout, the message from the community was clear: protecting the Harlem River is not optional.

The DEC will hold a public hearing later this month virtually on June 16 and in-person on June 18 to consider public comments. Advocates are urging residents to attend, submit comments, and keep the pressure on city and state agencies to deliver on long-promised clean water goals.

Shino Tankawa of the SWIM Coalition warned that reclassifying the Harlem River could set a dangerous president for the rest of the city’s waterways.

“Where do we stop?” Tanakawa said. “We’ll never reach the fishable, swimmable river that we all deserve to have. Reclassifying the Harlem River in this way gets the city of the hook from investing more resources into the communities that have experienced divestment for the last century.”