After a cancer diagnosis, patients are warned about the possibilities of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hair loss, weight loss, loss of appetite and depression – but few, if any, are cautioned about taste disturbances.

“My husband cooks and he had to change the way he was cooking. For example, si era pollo (if it was chicken), I didn’t like it guisao (stewed), I didn’t like it in the oven — everything was steamed, no sazón, no adobo, no garlic, no nothing,” said Milka Galarza of her side effects from the chemotherapy treatment she received after being diagnosed with stage 3 carcinoma breast cancer in 2017.

Galarza, who lives in the South Bronx and had an affinity for typical Puerto Rican foods prior to her treatments, admits that although her sense of taste has returned, “there are times when the food doesn’t taste like it did before.” Galarza has been taking letrozole — a drug to treat breast cancer — since 2020 and is prescribed to continue the medication until 2025.

“That’s a topic that we don’t cover that often, because we’re focused more on the hair loss and ‘you’re going to be nauseated’ and those types of things,” said Dr. Roshni Rao, chief of breast surgery at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

An independent 1993 study published in Behaviour Research and Therapy monitored female breast cancer patients who underwent emetogenic chemotherapy — chemo that induces vomiting. The study found that patients developed a repugnance, aka learned food aversions (LFA), to any foods they consumed within a 24-hour period of receiving treatments.

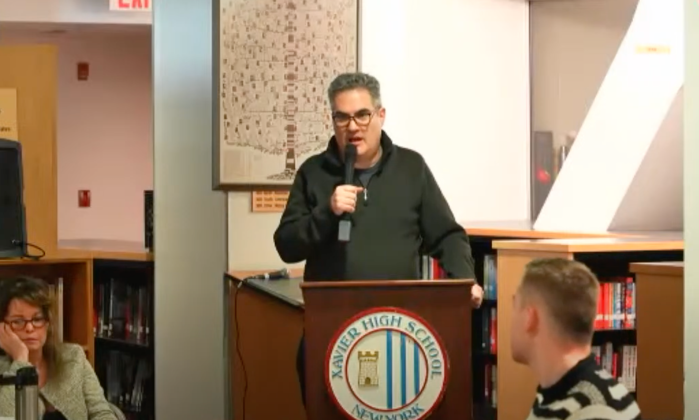

“Cancer patients do show these types of conditioned responses,” said Dr. Jan Mohlman, a clinical psychologist and professor at William Paterson University. Among other clients, Mohlman also works with people undergoing chemotherapy in order to help recondition the psychological associations they have made with receiving treatments.

Mohlman explained that many treatment clinics give cancer patients an offensive-tasting drink which is also referred to as a “scapegoat” food, prior to giving them emetogenic chemotherapy. This is because patients tend to associate vomiting from chemo with the last food they consumed, therefore the patient will psychologically correlate the nausea they are experiencing to the offensive-tasting drink. Ironically, she said some people tend to enjoy their favorite meal before receiving chemo because they expect to not have much of an appetite afterward.

“What ends up happening is that people become conditioned to avoid and dislike their favorite meal because they associate it with throwing up,” Mohlman added.

When Megan-Claire Chase from Georgia was diagnosed with stage 2 invasive lobular breast cancer in 2015, she was prescribed doxorubicin as her chemo treatment – also commonly referred to as the “Red Devil” due to its color. As a result, Chase says that she could not consume red-colored food or drinks for two years after her chemo treatments.

“Every time I would see something red, I just got ill,” she said. Chase had to coach herself through her psychological connections and convince herself that the red food and drinks were safe to eat.

Some patients complain of disliking their once favorite foods, having phantom taste — an often unpleasant taste even though there is nothing in your mouth — or even eating new foods they never liked before.

But it’s not just foods. Chase could not use silverware because the metallic sensation reminded her of the metal taste she would experience throughout her chemo treatments. She went years using plasticware. Adversely, Chase admitted to never being a coffee drinker before treatment, but now says, “I can’t go a day without it.”

Currently, there is no cure for these taste aversions brought on by cancer treatment. Although patients are normally appointed a nutritionist to help with diet, Chase said, “I don’t feel a lot of nutritionists in the cancer centers were really equipped to handle [taste disturbances] because it’s a psychological issue.”

Mohlman suggests that patients experiencing such intrusions should attempt to keep anxiety levels down as mood can influence the intensity of taste.

“We have a long way to go in treating these and other psychological aspects of cancer treatment,” Mohlman said.

Reach ET Rodriguez at elbatamarar@gmail.com. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes