Members of the Yemeni business community in Morris Park are fed up with having their stores broken into and believe bail reform is to blame.

On March 18, the Alliance of Yemeni American Businesses, the Bronx Community Council, clergy and residents held a press conference at 1907 White Plains Road in Little Yemen detailing their concerns on recidivism, quality of life and public safety. More than 500 Yemeni-owned businesses operate within a 1-mile radius of Little Yemen, which is wedged in-between the Van Nest and Pelham Parkway neighborhoods in the Bronx; but the heart of Little Yemen is located on White Plains Road at Rhinelander Avenue.

According to the NYPD, New York City saw a 38.5% increase in overall crime compared to January 2021, including the fatal shooting of two cops while responding to domestic violence call in Harlem. And members of the Yemeni community blame the recent spike on bail reform.

Yahay Obeid, the outreach coordinator for the Bronx Muslim Center, told the Bronx Times that in the past couple months there have been 10 break-ins at stores in Little Yemen. Obeid, who came to America in 1991, grew up in Harlem where violence was common — his father was shot there.

“When they break in the stores, they have nothing to lose because they know they’ll be out of jail in a couple of hours,” said Obeid, 38. “I feel like this is flashback from when I was a kid in the ’90s. We have to stop it. We have to protect our youth. We cannot let them out of jail to be put back on the street and commit the same crime.”

On April 1, 2019, New York state passed sweeping criminal justice reform legislation that eliminated cash bail and pretrial detention for nearly all misdemeanor and non-violent felony defendants. Bail reform, along with other reform measures, went into effect Jan. 1, 2020.

Business leaders and anti-violence groups who joined forces with the Yemeni community at the press conference said they have no issue with bail reform per se, but added that it must be accompanied by job placement, housing assistance, counseling, medical and mental health services programs to help people once they are released.

A Morris Park resident and retired NYPD lieutenant, Sammy Ravelo is tired of seeing criminals let back out on the streets is planning to walk from Morris Park to Albany for a rally on April 26 protesting bail reform.

“This bail reform law that luckily passed, it’s affecting all of our communities,” said Ravelo, who ran for Bronx borough president in 2021. “We have a beautiful Yemeni community and I’m starting to feel what’s happening on the other side of the Bronx. We have to be the generation that’s going to change.”

One example highlighting the issue was the recent release of a man who allegedly smeared human feces on a woman in the Bronx’s East 241 Street subway station.

Marion Frampton, president of The Black Spades New Direction, an anti-violence grassroots organization that was originally an African American street gang dating back to the 1960s, said bail reform at its core is fine, but there must be services for people when they are released from jail.

“We all say we believe in this bail reform, but it’s a joke because it was not put in place to save our kids’ lives,” he said.

Mercedes Broom, a fellow member of The Black Spades New Direction, said bail reform doesn’t solve the deeper issue that many Black and brown communities lack resources and programs for children. She said maybe if kids had more options after school, they would be less inclined to pick up a gun or commit crimes.

“Our children are reaching for guns because they have no books,” she said. “We’re more than basketball players. We are scientists and we are doctors. We need to invest in our community. We have to show our children that they are kings and queens.”

Gov. Kathy Hochul and NYC Mayor Eric Adams also want to make changes to bail reform. A recently leaked 10-point memo from the governor calls for increasing the number of bail eligible crimes to include certain gun, hate crime and subway offenses that currently only warrant a desk appearance. It would also allow judges to set bail based on factors like people’s criminal histories, their past use or possession of a firearm or if they’re a repeat offender. Hochul hopes to have these measures included in the upcoming state budget.

Additionally, the plan would make it easier to prosecute gun trafficking by lowering the threshold of the amount of guns one has to possess to be charged – bringing it down from 10 to three guns for a class B felony and five to two guns for a class C felony.

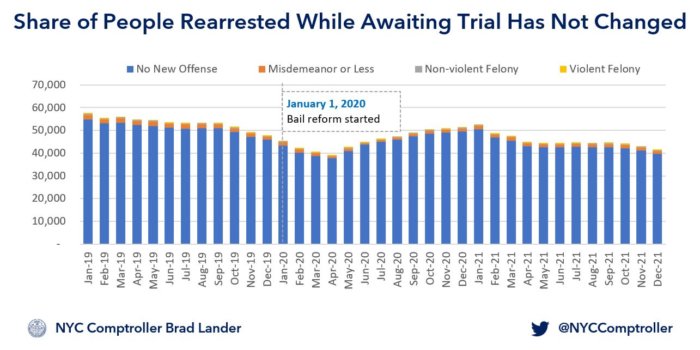

However, a recent report by the Office of the NYC Comptroller Brad Lander counters that bail reform is working. The report found bail reform legislation passed by the state Legislature in 2019 reduced the number of people subject to bail meaningfully, lowering the number of cases in which bail was set from 24,657 in 2019 to 14,545 in 2021. Meanwhile, the vast majority of people awaiting trial in the community were not rearrested on new charges.

The data indicates that pretrial rearrest rates remained nearly identical pre- and post-bail reform. Data released by the New York City Criminal Justice Agency and the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice show that the share of released people awaiting trial who are rearrested remained roughly the same before and after implementation of bail reforms. In January 2019, 95% of the roughly 57,000 people awaiting trial were not rearrested that month. In January 2020, 96% of the roughly 45,000 people with a pending case were not rearrested. In December 2021, 96% were not rearrested. In each of those months, 99% of people, regardless of bail or other pretrial conditions, were not rearrested on a violent felony charge, according to city data.

The Comptroller’s Office’s findings make clear, however, that additional judicial and prosecutorial accountability and oversight of the bail system are needed, with the aim of strengthening implementation of the reforms and reducing the pretrial population.

REPORT: In a moment of real anxiety about public safety, the conversation on bail reform has become divorced from the data.

Data shows essentially no change in the share of people rearrested post-release before & after the implementation of bail reform.https://t.co/WWxte3aIZ4

— Comptroller Brad Lander (@NYCComptroller) March 22, 2022

Reach Jason Cohen at jcohen@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4598. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes