With a dearth of fully serviced and staffed banks in her area, if Grand Concourse resident May Carter has to get to a bank, she tries her best to make the most of an at times hour-long commute where financial anxieties overrun her thoughts.

“If I gotta bank, it’s like a date. I feel like I need to get dressed up,” said Carter, 40. “I know I have to get into the city, get into nice clothes and possibly still get turned down for a loan or get hit with a withdrawal fee.”

Banks are far and few between in the South Bronx neighborhoods of Morrisania, Longwood and Melrose. It thins out even more along Morris Avenue in the western portion of the borough to Intervale Avenue and Fox Street in the east, and from Crotona and Claremont parks in the north to East 150th Street in the south, where patrons describe a barren wasteland of full-service financial hubs.

In the Bronx, seven banks closed 17 branches from 2018 to 2021 — more than half were in 2020 — reducing the total number of full-service branches to just 131, down from 144 in June 2018, according to The Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development.

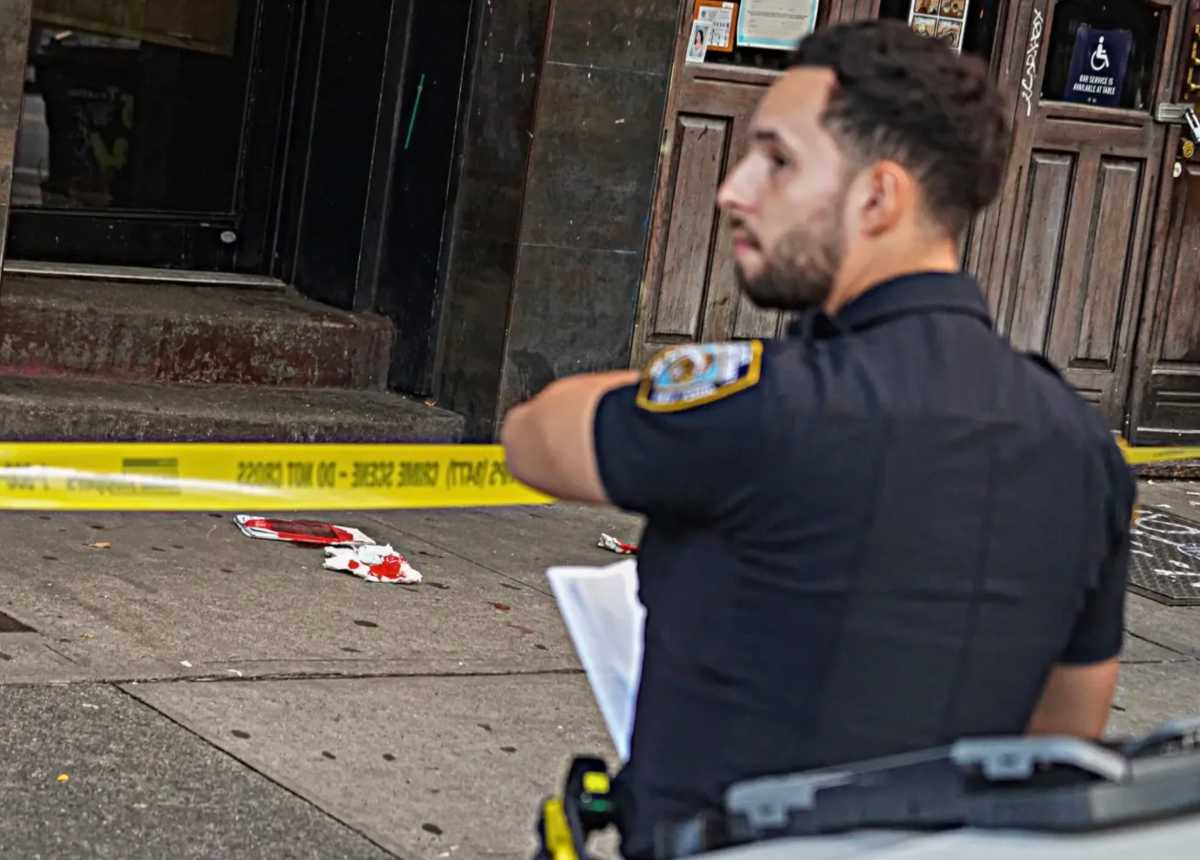

Without a full-service institution, bank-needy Bronxites rely on check cashers, pawn shops or branches of the largest national banks that typically charge high monthly maintenance fees for customers without direct deposit or certain minimum balances, multiple credit unions and Bronx residents told the Bronx Times.

“There are no branches,” said Gregory Jost, Banana Kelly’s policy and campaigns advisor. “Some say it’s a banking desert but you can call it a banking apartheid zone.”

And even Bronx hubs along Jerome Avenue, the Grand Concourse and University Avenue are scant on full-services branches.

The South Bronx — where 38% of its residents live below the poverty line — and Manhattan’s Lower East Side were victims of Depression-era redlining that cut off communities teeming with Black and immigrant communities from wealth-building opportunities and infrastructure.

While the Lower East Side eventually bounced back in the ’70s and ’80s, in large part to credit unions, the South Bronx is hoping the launch of a new mobile credit union— with hopes for a permanent location in 2023 — can lead to a similar revitalization.

The Bronx People’s Credit Union, an effort by multiple groups — Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, University Neighborhood Housing Program, We Stay/Nos Quedamos and the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation — aims to re-imagine banking “for the Bronx, by the Bronx.”

Recently closed banks are also joining the initiative hoping to fill gaps following their individual closures.

“We heard from our community partners that bringing a community development credit union to the Bronx would make a big difference and we listened,” says Karina Saltman, a senior managing director with Webster Bank, which closed its 149th Street in the Hub in August 2020 and is a partner in the credit union.

Others like New Covenant Dominion Credit Union, a minority-owned financial institution founded in 2007 by the National Credit Union Administration, seek to build once-forbidden wealth-building opportunities back into underbanked Bronx communities like bank-starved Morrisania to increase staffing and full financial service buildout.

More than 100 branches closed in 2020 in New York City, an increase from 74 closures in 2019 and 53 in 2018. While closures permeated throughout the city, a quarter of the 2020 bank closures were in low- and moderate-income census tracts, and 20% were in majority Black or Latino communities.

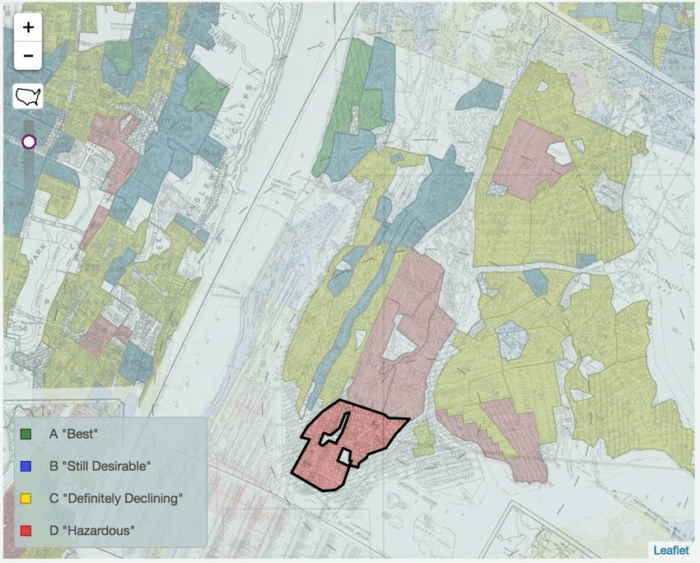

Many Bronx communities didn’t stand a chance when President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the New Deal and redlining became a central baseline for today’s racial wealth gap.

As the New Deal infused capital into cities and Robert Moses molded New York into his vision in the 1930s — the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) carved America into the unequal landscapes it is today.

In the Bronx, neighborhoods like Riverdale and Fieldston — which HOLC recognized as the newest, most suburban neighborhoods in the borough — achieved a green, type A status for investment. They were most desirable for what they did not have: communities of color.

Neighborhoods where Black people lived — the South Bronx in particular— were rated “D”, a scarlet letter that deemed these communities ineligible for federal investment and HOLC appraisals severely limited Black home-owners’ access to mortgage credit and home equity growth.

“They would say redlining is a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said Jost. “Banks write off the neighborhood because they say it’s a bad investment, but by writing off the neighborhood, it’s going to lead to the process of decades of our neighborhoods being underinvested and underbanked.”

The Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 primarily addressed redlining, but bank closures began to ramp up around the ’80s in the Bronx.

During the Great Recession, comparably sized banks closed at higher rates in markets serving communities of color between 2009 and 2014, with Black and Latino communities losing half their branches.

By 2015, according to an FDIC analysis of underbanked households, 30% of homes without a bank account resided in Mott Haven and University Heights.

And even in the face of bank closures — such as the December 2020 closures of two Popular Bank branches in Hunts Point and a 2021 closure of a Ridgewood Savings Bank location on Jerome Avenue — the pleas of residents fell on deaf ears.

The uneven distribution of bank branch locations exact a cost on residents of communities of color in the forms of greater travel distance and time to the nearest banking facility.

And mobile branches aren’t just met with the challenge of increase banking access boroughwide, but also improving banking experiences. For Black and Hispanic bankers, ATM, overdraft and routine service charges carry an extra and disproportionate cost.

NYU researchers in 2018 found that the minimum opening deposit was substantially higher in majority Black neighborhoods ($80.60) than in white neighborhoods ($68.50).

“Before, I would go to to the check casher and buy a prepaid card for $10. Then I’d have to pay additional money to load my money onto the card,” said Sonya Ferguson, the president of the Banana Kelly Block Association and a Bronx Community Board 2 member. “If I wanted to put $100 on my card, I had to pay $5. When I needed to take money off my card, I had to pay $2.50 to get my money, plus the $1 from the ATM. You end up spending the money you have just to use it.”

The road ahead for credit unions and Bronx wealth builders to reverse the harm of redlining and systemic underbankment in the Bronx is a long one, those tell the Times.

“We want this to go in the East Bronx, into these other communities that might have seen two or three of their branches disappear, and building this there’s a lot of possibilities and a lot of different neighborhoods or quadrants,” said Jost. “But we want to make sure we get it right with our first branch in the South Bronx before we build this thing and meet these borough-wide challenges.”

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes