Two Bronx parks are up for consideration for city landmark status — one of which would be the borough’s first-ever designated scenic landmark.

During Tuesday’s meeting of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), the board voted unanimously to calendar two Bronx sites — the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail stone walkway in Fordham and the Joseph Rodman Drake Park & Enslaved African Burial Ground in Hunts Point — the first step in the city’s landmark designation process. After sites are “calendared,” the LPC holds a public hearing for community input before casting a final vote.

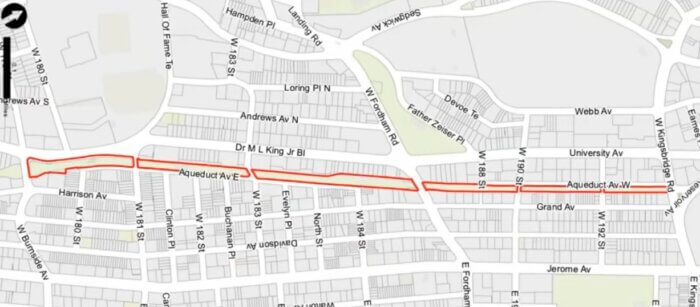

Sarah Eccles, a researcher with the LPC, presented her findings on the cultural and historical significance of the Old Croton Aqueduct Walk — which is a raised stone walkway along Aqueduct Avenue in the Fordham section. If designated, it would be New York City’s 12th scenic landmark, and the Bronx’s first.

According to Eccles, the aqueduct was built in the 1800s in response to a bad cholera outbreak in New York City during a time when many people didn’t have water to drink, clean with or use to extinguish fires. With the help of between 3,000 and 4,000 immigrants — most of whom were Irish — it was completed in July of 1842, and became available for public use in October of that year.

The 41-mile long aqueduct that ran from Westchester to Manhattan was the first-ever direct water source to New York City. By 1890 it could carry 340 million gallons of water to the city per day, which was enough to sustain the growing population.

The majority of the pipe is far underground, but there is a section of it with a visible raised earthen and stone embankment, Eccles said — which almost immediately became a public walkway for many New Yorkers, including Edgar Allen Poe. At the turn of the century, the community fought off multiple redevelopment projects including a 1903 proposal to put a trolley line alongside the aqueduct, “which would have disrupted this walkway in the developing Bronx,” Eccles said.

Later in 1929 when the city tried to sell the walkway to land developers the community also fought off the initiative, she said.

“This engineering marvel allowed New York City’s development to accelerate rapidly through the 19th century, during which the embankment atop the aqueduct became a favored public walkway,” Eccles told LPC commissioners.

The aqueduct walkway opened as a public space through the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation in 1940, equipped with sand pits, a playground, benches, as well as shuffleboard and horseshoe pits. It’s currently a 4.9-mile “shoestring” park still managed by the city department.

LPC commissioners were overwhelmingly supportive of turning the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail into the borough’s first scenic landmark.

“Highline ‘schmigh-line,’ I think we had it first and it’s a remarkable designation,” said Commissioner Michael Goldblum. “Hopefully we’ll be able to, over time, enhance the experience of this really, really cool piece of New York history.”

Commissioners also supported designating Joseph Rodman Drake Park & Enslaved African Burial Ground, located in the Hunts Point neighborhood southeast of the Croton Aqueduct, as an individual landmark.

Michael Caratzas, an architectural historian with the LPC, said the city has recently taken measures to more properly memorialize all the people buried at the site — no longer only recognizing the colonizers but also their enslaved African and Indigenous people.

“Today the park is both a site of major historical importance and a vital green space in an industrial section of Hunts Point, where it is ringed by warehouses adjacent to the Hunts Point food markets,” Caratzas told commissioners.

The park, originally named after American poet Joseph Rodman Drake, opened in 1910. But later through radar surveying, researchers realized that the park is actually the site of two colonial-era cemeteries dating back to the early 1700s — with undocumented graves of people of African and Indigenous descent. Caratzas said the studies even indicated a possibility of graves being exhumed and then reinterred.

In 2021, the park was renamed, which Caratzas said more properly memorializes people who “were central to the early history of Hunts Point in New York City.”

“Originally created in remembrance of Joseph Rodman Drake and the area’s colonial era landowners, Drake Park now recognizes enslaved people whose history in the area and final resting place within the park has long been unrecognized,” he said. “Research associated with this proposed designation may lead to a more inclusive landmark name.”

The LPC has yet not scheduled dates for public hearings for either proposal.

Reach Camille Botello at cbotello@schnepsmedia.com. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes