Advocates are renewing their push for a long-stalled bill that would double New York’s bottle deposit from five to 10 cents, allowing the city’s “canners” — individuals who collect bottles and cans and redeem them for the deposit money — to earn more for their efforts while helping reduce street litter.

Canners perform a vital, if often overlooked, role in the city’s waste system. They collect redeemable beverage containers from sidewalks, trash bins, and curbside recycling bags and return them to supermarkets, redemption centers, or kiosks in exchange for the state-mandated five-cent deposit.

That deposit amount has remained unchanged since New York implemented its bottle bill in 1982 — and advocates say it’s time for an update.

The Brooklyn-based nonprofit Sure We Can, which operates a container redemption center and champions the rights of canners, is among the groups backing the Bigger Better Bottle Bill. The legislation proposes three key changes: increasing the deposit to 10 cents, expanding the types of containers eligible for redemption, and raising the 3.5-cent handling fee that beverage distributors pay to redemption centers.

Despite growing support, the bill, sponsored by Assembly Member Deborah Glick and Senator Rachel May, has stalled in Albany for four consecutive years. It currently sits with House and Assembly committees.

Whether or not to increase the five-cent deposit has become the top sticking point in debate among lawmakers, canner advocates and the beverage industry.

The American Beverage Association said increasing the deposit “would impose additional costs on New York consumers already dealing with higher prices for housing, food, and gas and on local small businesses that are struggling to stay afloat,” according to a March 2025 memo.

Instead, the association supports a new version of the bill, sponsored by Sen. Christopher Ryan of the Syracuse suburbs and Assembly Member Amanda Septimo of the South Bronx, which would keep the deposit at five cents while funneling more money to the state’s redemption centers, among other efforts at gradually updating the recycling system. Septimo did not respond to request for interview.

Still, activists say the deposit increase is the most critical aspect of the bill and that momentum is building in favor of it. The Glick-May bill is co-sponsored by 17 state senators and 63 Assembly members, and backed by more than 200 community organizations, environmental groups, academic institutions, and redemption centers.

Advocates also say public sentiment is on their side. A Siena College poll released in April found that 61% of New York State residents — across party lines — support raising the bottle deposit from five to 10 cents.

‘Hidden in plain sight’

In New York City, canners are everywhere. While the exact number is impossible to determine, Sure We Can estimates there are at least 10,000 active canners “hidden in plain sight,” said Ryan Castalia, executive director.

A 2023 study highlighted the diversity of the workforce. Men and women were about equally represented in a survey of 38 worksites across the five boroughs, as were English speakers and Spanish speakers. The overwhelming majority were Black or Latino (87% combined).

Canners are an older workforce, with an average age of 54, according to the study. It also showed that many of them face barriers to traditional employment, most commonly a mental or physical health challenge or lack of identification or documentation.

Virtually anyone can participate as a canner, as it is an “extremely low-barrier way to work,” Castalia said.

However, the job is “dirty and hard” and comes with many health and safety concerns, he said. The work can be physically intense, requiring a lot of walking, bending and handling messy and sharp objects in all weather conditions.

On a recent visit to canners at East 135th Street and Willis Ave. the South Bronx, a woman named Zulma, who is retired from her job cleaning NYCHA apartments in Manhattan, told the Bronx Times she makes $60 to $70 per week and has been canning for more than 10 years.

Collecting that day’s haul of cans and bottles took her three days — six or seven hours at a time — “from the morning to the night,” she said.

Zulma’s experience was reflective of those in the study, which showed canners worked an average of 25 hours per week, and 63% earned $100 or less.

As housing, food and other necessities have become increasingly expensive, many like Zulma use canning to supplement their regular income or, in some cases, as a standalone job. But with only a five-cent deposit, they make little money relative to the real risks involved.

Zumla said she sometimes worries about her safety while out collecting. “It’s dangerous for a woman,” she said, but added, “thanks to God,” nothing bad has happened.

Most of the 10 or so canners there with her were women. Zulma said she believes women work harder than men and will endure the physical hardship. “Old lady that can hardly walk, she does it.”

Modernizing the recycling system

In New York’s informal economy, canners play a vital environmental role, diverting millions of bottles and cans from landfills and city streets. In 2023 alone, more than 12 million containers were redeemed at Sure We Can’s Brooklyn redemption center — many of which would have otherwise been improperly discarded.

Advocates say the Bigger Better Bottle Bill would not only benefit canners and struggling families but also deliver significant financial and environmental gains for New York City and state.

Under the current system, the state receives 80% of the money from unredeemed deposits — providing a revenue stream even when containers aren’t returned. But modernizing the program could yield even greater savings, according to a 2025 report by the think tank Eunomia.

The report estimates that the changes in the Bigger Better Bottle Bill could save New York municipalities at least $40 million annually, and potentially up to $100 million, by reducing the cost of curbside recycling. New York City alone could save between $35 million and $80 million each year, it said.

Improving incentives works, supporters argue. New York’s current beverage container recycling rate is roughly 70%. With an updated law, it could rise to 80–90%, mirroring results in Oregon, which saw redemption rates spike after raising its deposit to 10 cents in 2017.

The bill, given the 5-cent increase, also proposes raising the 3.5-cent handling fee that beverage distributors pay to redemption centers — a crucial provision, advocates say, at a time when many centers have shut down and those that remain are struggling financially.

Another major update would expand the types of containers eligible for redemption. When the original deposit law was enacted in 1982, the beverage market looked very different. Today, popular drinks like Gatorade, Snapple, and coffee beverages fall outside the program and often end up in landfills or as street litter. The Glick-May bill would include more types of containers, excluding only dairy and 100% fruit juice.

Supporters say the expansions would benefit canners, the environment, and municipalities — but the beverage industry disagrees.

In a March 2025 letter to members of the New York State Assembly, the American Beverage Association and New York bottlers expressed concern about imposing an additional five-cent upfront cost to consumers. Having to pay a deposit of $2.40 on a 24-pack of beer or soda, for instance, would “hit working families hardest,” the letter said.

The letter also said that while the industry encourages recycling and the “circular economy” around bottle deposits, increasing bottlers’ handling fee from 3.5 cents to 5 cents would be expensive for those companies and do nothing to improve the state’s recycling system, which “lags in innovation and investment” compared to other parts of the world.

Lastly, the beverage industry says fraud is a problem because people are redeeming money on beverages purchased in a neighboring state that has no deposit system. Doubling the bottle deposit would also double “the incentive for fraud,” the letter said. The American Beverage Association said it already sees “massive redemption fraud” on the New York-Pennsylvania border, for instance, which can cost businesses, consumers and state tens of millions of dollars per year.

“Consumers end up paying for the refunds and handling fees paid out on these fraudulent returns,” the letter said. The new version of the bill under Sen. Ryan and Assembly Member Septimo, supported by the beverage industry, aims to close loopholes that enable unlawful redemption.

But advocates for the Bigger Better Bottle Bill say industry concerns are overblown. Fraud is not the real issue, but corporate resistance is, they say.

“This bill benefits everybody except for ‘Big Beverage,’” Castalia said.

Hearing from the canners

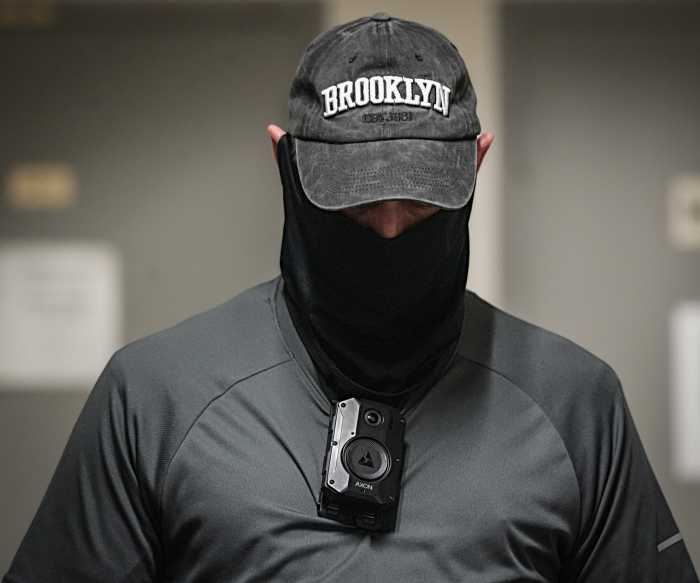

During the Bronx Times’ visit in the South Bronx with Sean Basinski, communications director for Sure We Can, who served as translator, it was easy to see the unregulated and informal nature of canners’ work.

At 9:00 a.m. on May 23, eight or 10 people waited along East 135th Street and Willis Ave. with giant, clear plastic bags stuffed with cans and bottles lined up along the sidewalk.

Most bags were labeled with the number of containers inside, usually 200 to 300 each. Canners said they have to provide their own bags.

Every Monday and Friday between 10 and 10:30 a.m., a truck driver comes by, takes each collector’s bags and gives them cash in return. Canners explained that the driver trusts everyone to provide an accurate count, noting that he recognizes the regulars. He then drives the bottles and cans to be recycled in Brooklyn.

The system works smoothly. There is no nearby redemption center in that part of the South Bronx, and it’s impossible to travel far with massive bags, so this is their best bet, the canners said.

That day’s workers included a man pushing bags in an overflowing shopping cart, with his dog walking alongside; Jesus, who said he has diabetes and suffered a fall, leaving his right leg in a split held in place with pins; and Sergio, who said he has knee problems.

“It’s a little hard, we have to walk all around,” he said.

A woman named Faustina, who said canning was her only source of income, had walked two hours with five huge bags stacked on a hand cart. There was no option closer to where she lived, she said.

Her problem is common: many redemption centers have gone out of business, leaving none in the entire borough of Manhattan, for instance, according to Sure We Can.

One canner had a very specific use for the money she earned that day. Maria, 76, said throughout her year of experience, she has used the income — about $25 every two to three weeks — to buy food for stray cats in the neighborhood.

She previously worked as an ice cream vendor but is now retired, and her Social Security income is only $285 per month, she said.

Maria flipped through photos on her phone of her many rescued cats and said she was disturbed by how people mistreat them in the neighborhood. “People are no good,” she said.

But whether she earns five or ten cents per can, she said she would continue helping the animals. “Of course, I always help them. Outside, there’s a lot of them that are hungry.”

A few of that day’s canners were aware of the Bigger Better Bottle Bill and the push to help them make more money.

Maria Elena and her husband Carlos, who split a sandwich and drank coffee while waiting for the truck, said they come to this corner every 15 days and earn about $40 per week.

Of the proposed deposit increase, “Of course, this would be good,” Carlos said. “Five cents is nothing.”

“When are they going to increase the money for bottles?” Maria Elena asked.

But Zulma, the retired NYCHA worker-turned-canner, said she doesn’t have much hope that elected officials will make it happen.

Castalia with Sure We Can agreed that it was a “big task,” and there are always many competing priorities.

But the organization will only support a version of the legislation that raises the deposit to 10 cents, which he said is “the most fundamental aspect of the bill.”

“It’s what drives participation, it’s what actually makes the environmental outcomes happen, it’s what gives canners income, it’s what incentivizes people to participate. So a program update without a deposit increase is not a serious proposal,” he said.

Zulma said she believes politicians are “no good” when it comes to supporting people like her. “Once you get them [elected], that’s it.”

Reach Emily Swanson at eswanson@schnepsmedia.com or (646) 717-0015. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes