A growing staffing crisis—driven by low wages and high turnover—is putting vital services for severely disabled people in jeopardy, both in the Bronx and across New York City, warns Rupert Pearson, executive director of the Southeast Bronx Neighborhood Center (SEBNC).

At the heart of the crisis are Direct Support Professionals (DSPs), the frontline caregivers responsible for assisting more than 130,000 New Yorkers with severe disabilities. These workers play a crucial role in ensuring the safety, dignity, and quality of life for their clients—yet many of them could earn more working at fast food restaurants.

DSPs perform demanding, hands-on work: helping individuals eat, take medications, change diapers and navigate daily routines. Their care often extends beyond the basics, offering educational and recreational support to people with complex needs, including those with autism, Down syndrome, and cerebral palsy.

Despite the critical nature of their work, DSPs in New York City earn an average of just over $18 an hour. Most are employed by nonprofit organizations, with salaries ranging between $35,000 and $40,000—comparable to what a cashier or maintenance worker might make at a fast-food chain, according to job site Indeed.

Pearson said he leads a staff of 40 DSPs who start at $19.75 per hour — a wage recently increased in an effort to recruit more workers to his team. Many Bronx-based agencies pay around $17, little more than the city’s $16.50 minimum wage, he noted.

DSPs have long been underpaid — and Pearson would know, having started his career in that role in 1991. He told the Bronx Times that little has improved in the industry since those days, but his organization remains “heavily invested” in bolstering the DSP workforce.

Another major obstacle, he said, is the pay gap between DSPs employed by nonprofit providers and those working in state-run group homes. According to the state Office for People With Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD), DSPs in state-operated facilities start at $49,457 per year, plus benefits—significantly more than nonprofit salaries.

This disparity has been a longstanding issue, with nonprofits like SEBNC forced to strain their budgets to make wages more competitive.

“Unfortunately, [the state] controls the purse strings for all of us,” since it sets the norm for what DPSs may expect, said Pearson.

A critical workforce

DSPs are essential to providing individualized care for many thousands of New Yorkers, and the Bronx has the city’s highest rate of disabilities in people under age 65 at 12.2%, according to Census data.

SEBNC offers Medicaid-funded day programs and a residence for those with severe developmental disabilities. Its DSPs help with medication administration, transportation, activities, meals and outings, and they serve 120 adults, the oldest of whom turns 80 this summer.

Disability advocates have long lobbied for significant DSP pay increases to help stabilize the sector. This year, advocates were disappointed after calling for a 7.8% cost of living increase for both state and nonprofit DSPs but receiving only a 2.6% increase in the 2025-06 budget. Pearson said he hasn’t yet received communication on this increase or how the funds are to be used.

The state OPWDD said in a statement to the Bronx Times that Gov. Kathy Hochul has invested heavily in the DSP workforce since 2022, totaling $3.9 billion for nonprofit providers and career advancement infrastructure. She recently invested $850 million to fund rate increases for providers, mainly aimed at boosting salaries, the office said.

But Pearson said it remains difficult for nonprofits to attract DSPs when the state pays more, and lawmakers have called for the state to take action on the issue. Assembly Member Angelo Santabarbara and Sen. Patricia Fahy introduced bills in their respective chambers to achieve pay parity under a new wage commission.

When it comes to hiring, not everyone has the patience and temperament to work as a DSP, even if they will accept low pay. But on the other hand, there are relatively few barriers to entry, and a college degree is not required.

SEBNC requires DSPs to have a high school diploma and 1-2 years of experience. The organization’s job posting for day program DSPs lists first aid training and knowledge of both English and Spanish as a plus, and it emphasizes personal traits, such as calmness, dependability and teamwork.

At SEBNC, staff are great at their jobs but are experiencing real economic hardship, said Pearson. His DSPs are all people of color, mostly women, and the workforce nationwide is 71% women. Most nonprofit DSPs—and even higher-level administrators—have second jobs to make ends meet.

His employees’ goodwill should not turn them into martyrs, Pearson said. “People do love the work, but they also have to eat.”

DSPs in action

During the Bronx Times’ visit to SEBNC on May 29, Pearson led a tour of the two-story group home on Third Ave. and East 164th Street, which has a lobby with comfy couches and a TV and six units upstairs, each with its own bedroom, arranged around a common kitchen and living room.

The group home for six individuals with disabilities is staffed 24 hours per day, and residents can decorate and request furnishings that meet their needs. Most rooms had only the basics, but one resident showcased a more elaborate style, with a Yankees sign on the door and a room filled with sneakers, hats and basketball posters.

It’s important for the space to be comfortable for each person, as Pearson said residents nearly always stay for the rest of their lives. “This is home for them.”

Across the street from the group home is the day habilitation program. Pearson went from classroom to classroom, visiting all six groups and greeting DSPs and individuals receiving service with hugs and handshakes.

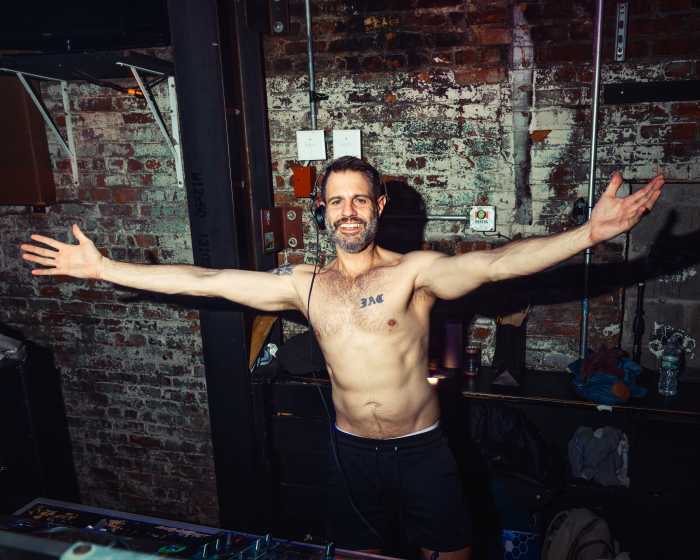

Many were still buzzing with the excitement from the day before, when they had participated in a semi-annual “Fun Day,” complete with a DJ, games, food and giveaways, such as SEBNC shirts and water bottles.

But a “Fun Day” every few months may do little to help DSPs stay on the job, where they often contend with unpredictable emotions, physical and communication challenges and occasionally violent behaviors.

SEBNC lost 12 DSPs after the height of the pandemic, Pearson said. “The pay being what it is, people are not willing to come back.”

Stephanie, who didn’t provide her last name but has been a DSP for 18 years, said she sometimes deals with unpleasant situations, but staff work hard to build good relationships with the individuals they serve. Once they get to know the job and the people, “It’s not as hard as it might look,” she said.

But Program Director Gail Brown emphasized that the job is highly complex because DSPs must get creative in every interaction — especially with those who can’t speak or communicate well.

“It’s a different teaching mechanism everyday,” she said.

Struggles for compliance

The challenge of recruiting and retaining good DSPs is just one issue Pearson is up against, as nonprofits also struggle to keep up with changing state regulations.

In his view, the state does not proactively inform providers of changes, and nonprofits often end up learning the hard way that they’ve failed to fulfill a new requirement.

“Many times, we only know there’s a change when we get cited,” he said.

For instance, Pearson said, when OPWDD began requiring diabetes training, he thought his organization was covered because diabetes care was incorporated into their standard first aid training. But the state expected staff to complete a standalone diabetes training — and SEBNC got cited for not completing it.

Pearson said nonprofits must constantly search for new requirements that pop up — and when they do, they must make arrangements to cover for DSPs to attend trainings.

On this issue, plus low pay, Pearson said little has improved over his 30-plus years in the industry. “It has always been this way.”

Looking to expand

Recognizing the DSP workforce crisis, the state and its local partners launched a recruitment campaign last year called “More Than Work,” which lists hundreds of agencies hiring DSPs throughout New York. The campaign has drawn 55,000 applicants for various agencies throughout New York, state sources told amNewYork in May.

As SEBNC tries to expand its own workforce, increasing pay for DSPs is only part of the effort. Pearson held a recent hiring event that drew 25 applicants and resulted in seven job offers.

But while becoming a DSP is fairly simple and more are desperately needed, Pearson said not everyone has the patience and skill set for this line of work.

To ensure each applicant is a good fit, some individuals receiving SEBNC services are asked to help facilitate hiring interviews. If they don’t believe an applicant will work out, the person will most likely not be hired, Pearson said.

Staffing challenges are top of mind these days, especially given the uncertainty around drastic cuts to Medicaid, which funds SEBNC’s residence and programs.

SEBNC is also starting construction on an eight-person group home on Sherman Avenue in the Bronx, which Pearson called a “massive undertaking” even though the nonprofit already owned the property.

As the home undergoes various state approvals and funding hurdles, SEBNC keeps pressing ahead on behalf of those who need their intensive services.

“If we weren’t in the position for a bank to give us money, those eight individuals would have nowhere to go,” Pearson said.

Even when the house is approved and ready, he still has to staff it. Finding applicants who are well-suited to the job is critical, but also, “We have to give them a reason to say, can I support my family?” said Pearson.

Without better pay and a more stable workforce, DSPs may have a harder and harder time sticking around through the rough days. “Some people say, ‘You know what, I’m not getting paid enough to take this abuse,'” said Pearson.

Reach Emily Swanson at eswanson@schnepsmedia.com or (646) 717-0015. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes