The opioid epidemic has had a devastating impact in New York and COVID-19 has made the problem worse, according to outreach workers with Acacia Network’s Bronx Opioid Collective Impact Project.

They are intervening in more overdose incidents and have seen an increase in opioid users in community spaces due to community treatment services being halted.

Acacia, a leading provider of substance use services across New York, launched the program in 2018. Workers conduct regular outreach throughout the Bronx to provide free Narcan overdose prevention training, syringe exchanges, referrals to social services and health programs, as well as other resources.

“When we encounter an individual who is ready to enter a detox program we help them,” said Mayra Herrera, program director of the Bronx Opioid Collective Impact Project. “We have seen a positive impact in the work we’re doing.”

According to the New York State Health Department’s 2019 New York State Opioid Annual Report, opioid overdose deaths increased 200 percent between 2010 and 2017, while the Bronx was one of 16 counties with the highest rate of opioid abuse and overdose deaths.

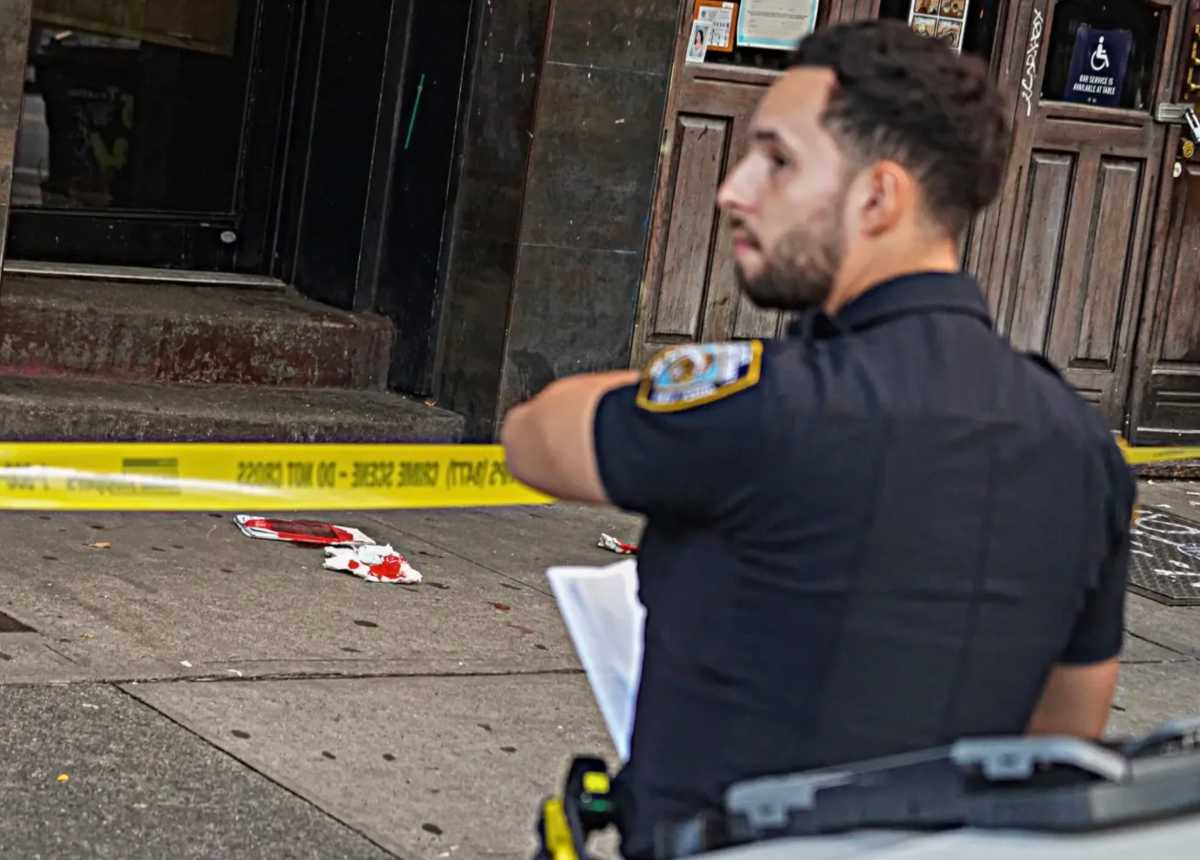

Herrera told the Bronx Times that due to high drug activity between 149th Street and Third Avenue, the nonprofit has deployed its outreach workers in that area.

The program’s work, which is completely funded by the City Council, is even more important now after the state slashed drug abuse treatment funding by 31 percent this summer.

To date, the Bronx Opioid Collective Impact Project has:

- Distributed approximately 74,000 clean syringes, 1,400 condoms, 500 personal hygiene and first aid kits and close to 32,000 harm reduction items, including safe injection accessories, Fentanyl kits, safe smoking pipes, sniff kits, wound kits and survival bags.

- Picked up close to 12,000 used syringes.

- Provided close to 600 Narcan training sessions.

Herrera has been with the organization seven years and works with the HIV/HCV population and provides support and oversight to the Bronx Opioid Collective Impact Project to provide easy access to care and treatment.

She stressed that they cannot force people to get help — it’s something they have to want to do. All the program can do is offer guidance.

“Are they ready to commit to stop using?” she said. “You have to build a relationship with the community.”

Now more than ever with people out of work and struggling emotionally due to COVID-19, peer outreach workers like Shaun Nichols play a pivotal role in the program.

Nichols, 55, initially came to the Acacia Network as a patient and received support and services through substance use and addiction treatment programs. Once he became fully committed to his recovery, he decided he wanted to give back to the community and help others like him get the help they needed.

“This is why I do the peer support work,” Nichols said. “I can identify with active users and understand what they are going through on any given day.”

Nichols grew up in Brooklyn and wished there was a program like this when he was younger. He said that his work made a difference even though he had only been with the Collective for four months.

As a resident of the Third Avenue Hub for 11 years, he grew to know the community and also understood the struggles of the homeless community as a formerly homeless individual.

“I sleep well at night knowing I’m able to help people,” Nichols explained. “I owe Acacia Network my life.”

According to Nichols, his goal is to not only keep people safe, but to put a smile on their faces. He said that his favorite part of the job is talking with people and learning about their circumstances. Often the people come to him in tears and he does his best to calm them down.

Nichols noted that some people may not want help, but he understands it is a process.

“I tell them I’m no different than you guys,” Nichols said. “I let them know we’re not the enemy. I wish we could be out there every day.”