A young boy has a new grasp on life thanks to a state-of-the-art medical device.

Jacobi Medical Center recently created a prosthetic arm and hand using 3D printing technology for its youngest patient yet.

Born without forearms or hands, three-year-old Isaac Cruz is adjusting well to his artificial appendage dubbed ‘Mano,’ meaning ‘hand’ in Spanish.

Cruz’s arms were stunted in utero due to congenital amniotic bands.

Amniotic band syndrome is a rare condition caused by strands of the amniotic sac which separate and entangle digits, limbs or other parts of the fetus.

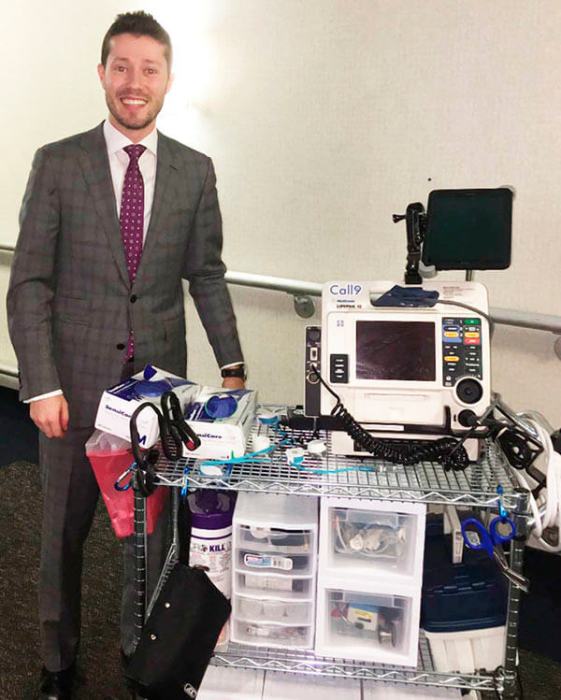

Jacobi plastic surgeon and burn fellow Dr. Cesar Colasante measured Cruz for the device via measuring tape and photogrammetry scanners.

Using the measurements, he custom-designed a prosthesis using CAD/CAM software, imported Cruz’s scan and modeled the parts in contact with the youngster to be a perfect fit.

3D printing molds narrow plastic pieces together creating a three dimensional image to the specifications created in a computer model.

“This is probably the first one like this made for such a young patient,” remarked Dr. Colasante.

Cruz’s attending physician, Dr. Ralph Liebling, chief of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Jacobi, supervised the work.

Since reimbursement models for 3D printed prosthetics are not yet established, Dr. Colasante paid out of pocket for wires, elastics, screws, a harness and spool of polylactic acid for two versions of the prosthetic.

Dr. Colasante and Dr. Andrew Peredo labored evenings and weekends designing and constructing Mano.

Several sessions were required to fit and adjust the device for Cruz’s preference.

The system allows Cruz to close the prosthetic hand by utilizing one arm to position the artificial appendage while the other pulls a trigger to grasp items.

An earlier model required bringing his shoulders forward to pull a wire extending from Cruz’s shoulders attached to a back harness in order to grab objects.

The elastic bands on this version provided more resistance than necessary.

Doctors noticed Cruz instinctively attempting to activate the grip using his other arm, however the device was not designed for that purpose.

Dr. Colasante returned to the drawing board to make Mano work as how Cruz wanted.

Weeks after receiving the newest model, Cruz’s father, Alan said his son has become accustomed to the colorful device which he proudly displays to his friends.

“Dr. Colasante really helped Isaac with creating this device,” expressed Alan. “He’s a great person and this arm has helped Isaac a great deal with his everyday tasks.”

Doctors estimate Cruz will outgrow Mano in six months to a year, but since he is pioneering this device it’s unknown how many times Mano can be recalibrated before upgrading to a newer model.

For Cruz’s other arm, Dr. Colasante is designing a myoelectric prosthetic which senses muscle contractions to send a signal to a computer board driving a motor to close the hand.

Approximately 20 Jacobi patients have received 3D printed prosthetics since the hospital pioneered the innovative process in 2015.